On September 19, 1991, a couple of tourists were hiking through the alpine mountains that straddle the border between Austria and Italy when they came upon a grisly sight – a frozen body with the lower half completely encased in ice. They initially thought they discovered the remains of an unfortunate mountaineer who maybe got lost or injured and died in the snow. Or perhaps they stumbled onto something a bit more blood-curdling like a murder victim. Either way, they did what any sensible person would do and alerted the authorities.

As it turned out, their suspicions were off by a few thousand years. A murder victim? Maybe (more on that later), but definitely not a recently-deceased mountaineer. The body belonged to a man from the Chalcolithic, better known as the Copper Age. He has often been referred to as Ötzi the Iceman, named after the Ötztal Alps where he was found and became somewhat of a sensation with him being the oldest natural mummy in Europe.

Today we are doing something a bit different here at Biographics as we explore the story of a man completely absent from the historical record. There are no texts, no inscriptions, no oral history to provide us with information about his family life, his accomplishments, or his failures. Every single thing we know about Ötzi, we learned by studying his mummified body and the items he had on him when he died.

The Discovery

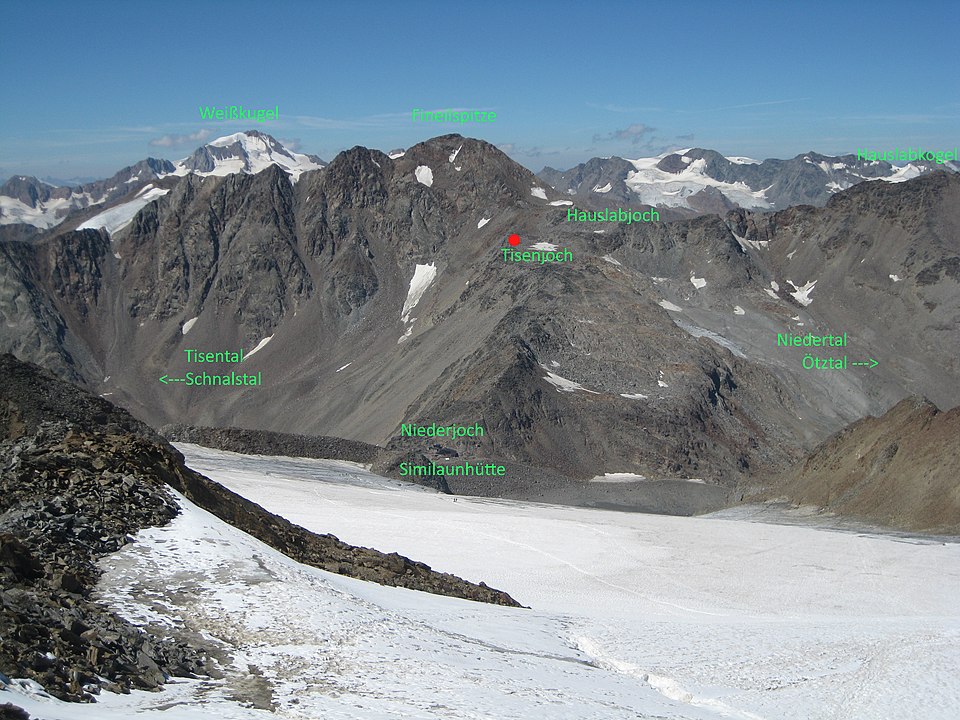

As we mentioned above, the iceman was discovered by two German hikers named Helmut and Erika Simon on the ridge of the Fineil peak, at an elevation of 10,530 feet. The two tourists were venturing off the beaten path when they encountered Ötzi’s half-thawed body so it is hard to say with certainty when he first emerged from his icy tomb. Most likely, it was that year’s warm summer that caused enough ice to melt to allow the head and torso to protrude out.

The discovery site of the man from the Tisenjoch (Ötzi) in the mountains of the Ötztal Alps. Credit: Mai-Sachme – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0Extracting the mummy from the snow proved trickier than expected. The first day, the Simons found the body but made no attempt to remove it. The second day, they brought a few policemen who came armed with pickaxes and a pneumatic drill, but they had to abandon the mission due to bad weather. The third day, another attempt was aborted because they could not obtain a helicopter. It wasn’t until September 23 that Ötzi was completely extricated from the ice and taken to the Institute of Forensic Medicine in Innsbruck. There, archaeologist Konrad Spindler dismissed notions that the body belonged to a recently-deceased mountaineer and said that it was 4,000 years old, at least.

Scientists realized the potential magnitude of the find and multiple teams went back to the location where Ötzi was buried and continued excavations to see what else they could discover. Meanwhile, four separate scientific institutions were given tissue samples from the corpse to perform radiocarbon dating and they all concluded that the ice mummy lived sometime between 3350 and 3100 BC. To put that into some perspective, Ötzi had already been buried for over 600 years when the ancient Egyptians began construction on the Great Pyramid of Giza.

In the meantime, modern authorities were more concerned over the complicated issue of ownership. With little regard for future geopolitical sensibilities, Ötzi decided to die right next to a somewhat-controversial border between Austria and Italy. According to the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye from 1919, the border between North Tyrol (which is in Austria) and South Tyrol (which is in Italy) is defined as the drainage divide of the rivers Inn and Etsch. However, when it was time to officially draw the borders on maps, the survey team made a mistake due to heavy snow and placed the border incorrectly. As a result, Ötzi was dug up by Austrian authorities and taken to an Austrian institute for study. However, two weeks after his discovery, on October 2, 1991, a new survey was carried out which determined that the mummy had actually been located about 300 feet from the border, but on the Italian side. Therefore, South Tyrol successfully claimed property rights, but agreed to let the scientific examination of the iceman be carried out in Austria. Consequently, Ötzi has been at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Italy for over two decades.

What We Learned from the Body

Ötzi, or the Similaun Man as he is sometimes called, is categorized as a wet mummy. This means that its body was dehydrated and lost most of its fluid, but the tissue and organs are still well-preserved.

Ötzi’s corpse has become one of the most extensively analyzed and examined human remains in history and, believe it or not, we are still learning new stuff about him and the age he lived in. We are fortunate that he was preserved almost in his entirety because he ended up in a crevasse that shielded him from the harshest weather elements, but also perfectly encased him inside a glacier and protected him from being crushed during the glacier’s movements. As a result of this, we got an amazing glimpse into the life, the behavior, the clothing, the tools, and even the diet of primitive Europeans from over 5,000 years ago.

Ötzi was a relatively small man for the time. His mummy is a little over 5 ft tall and weighs close to 29 lbs. In life, he would have been a bit taller, something like 5 ft 2 in, and would have weighed around 110 lbs. By examining structural bone units called osteons from the mummy’s femur, researchers estimated that Ötzi was around 45 years old when he died.

Most of his hair was gone because the epidermis quickly shed during the process of decomposition. However, a few clumps were still present around the remains, indicating that Ötzi had dark, medium-long hair with traces of arsenic in it. That last part suggests to researchers that the iceman was involved in smelting, most likely copper since he had an axe blade that was almost pure copper. This belief was further strengthened by the fact that Ötzi’s lungs were blackened by soot due to close, prolonged exposure to open fires.

Australian scientists from Canberra examined the isotopes in Ötzi’s teeth and bones to see what information they could glean. By studying the minerals present in his body, researchers extrapolated the composition of his drinking water and, consequently, identified the places where he lived.

They believe they pinpointed his origins fairly accurately and, unsurprisingly, they are not far from the site where he was discovered. They ascertained that the iceman lived somewhere in the valleys within 37 miles south of his icy grave. Moreover, they detected contrasts in the isotopic compositions of his tooth enamel which suggested that, at one point, he left his childhood home behind and moved around as an adult.

The rest of his bones suggested that the Similaun Man led a tough, physically-active lifestyle. He had broken several bones during his lifetime and x-rays revealed that his shoulders, knees, hips, and spine all had significant wear and tear in the joints. One study indicated that the iceman’s tibia showed mediolateral strengthening well above the average for late Neolithic men, something that could have been indicative of long walks over rough terrain. This, compounded with the rest of the physical stress exerted on his bones, led to speculation that Ötzi may have been a high-altitude shepherd.

How Healthy Was He?

This should not come as much of a surprise to you, but Ötzi was not a particularly healthy individual, at least not by our standards. In fact, he currently holds the distinction for oldest evidence of Lyme disease, an infectious illness which is transmitted to humans by the Borrelia bacterium spread by ticks. Scientists could not tell how advanced the infection was, but it could have given the iceman joint pains and severe headaches.

In addition to his bacterial companion, Ötzi was also infested with Trichuris trichiura, a parasite better known as whipworm. Eggs belonging to the parasite were still located in the iceman’s intestinal tract.

Perhaps the most curious medical affliction that befell Ötzi was severe arteriosclerosis. This is a hardening of the arteries which scientists previously regarded as a problem of the modern world. Specifically, it is usually an issue for people who follow the couch potato/fast food lifestyle as being overweight and getting little exercise were considered the major risk factors, alongside smoking and drinking. And yet Ötzi feasted on no fast food and reposed on no recliner, but he was still a heart attack waiting to happen. As it turned out, he had a genetic predisposition for arteriosclerosis, something which plays a bigger part in the condition than we previously expected.

Ötzi was also lactose intolerant, but this was still the norm amongst Late Neolithic Europeans. Dairy products represented a relatively new food group and their systems were still learning to process them.

In addition to all these, the iceman also had a few peculiarities that weren’t necessarily bad, just unusual. He only had 11 pairs of ribs instead of 12, he had an abnormally thick bony ridge above his eyes and lacked wisdom teeth. The rest of his teeth, you won’t be surprised to learn, were full of cavities and worn down, most likely due to his high-carb, grain-heavy diet. So, all in all, Ötzi wasn’t exactly the picture of health.

The Last Meal

Speaking of his diet, the iceman’s remains were so well-preserved that they still contained Ötzi’s last meal. It seems that just hours before he died, the Similaun Man gorged on a high-fat feast that would put most fast food menus to shame. We don’t know whether this was a regular occurrence for Ötzi or whether he realized he was dying and decided there was no point in letting good food go to waste.

Most of the meal consisted of fatty ibex meat. In its condition, it still had striations on the meat fibers which were a sign that it had been air-dried or cooked at low temperatures to last longer. Modern tests indicate that boiling the meat or roasting it or preparing it in any way using temperatures over 60 degrees Celsius or 140 degrees Fahrenheit would cause that striated pattern to disappear.

Ötzi complemented his ibex meat with a side of red deer. We’re not sure what part, though. While the ibex meat was clearly fatty muscle, the red deer meat he ate was, most likely, an organ like the spleen or liver. His stomach also contained traces of einkorn wheat.

Most curiously, it appears that the iceman also feasted on a type of fern called bracken which is mainly notable for being toxic. Researchers are still a bit puzzled over this one and haven’t found a conclusive explanation yet. Was it simply a mistake and Ötzi thought it was something else? Did he use it to wrap his meat and accidentally ingested a few pieces? Did he actually use it as medicine to treat a stomach ache? Or, again, maybe he realized he was dying and just thought “Might as well. Things can’t get any worse.”

The Tattoos

An interesting aspect about the Similaun Man’s body was that it was covered in tattoos. Originally, scientists spotted somewhere around 40, but that number steadily increased as they continued to inspect the remains closely and found new ways of contrasting the black tattoos against the dark, leathery brown skin. As of the most recent mapping of Ötzi’s body which took place in 2015, researchers spotted 61 tattoos grouped into 19 different sections.

The tattoos themselves are very basic and consist of black lines arranged either in cruciform patterns or parallel to each other. They were probably made by cutting small incisions into the skin and rubbing in charcoal.

Admittedly, the tattoos didn’t exactly turn Ötzi into the Illustrated Man, but scientists are more interested in their purpose rather than their quality. Were they purely for decoration, did they have some kind of symbolic or ceremonial meaning or was it possible, perhaps, that their purpose was medicinal?

That last option has really intrigued researchers ever since they noticed that all of the tattoos are grouped into clusters and placed on Ötzi’s lower back, wrists, ankles, and knees – all places that suffered degeneration and likely to cause pain. Perhaps they were used as an ancient pain relief treatment similar to acupuncture, only thousands of years before the practice was used in China.

Vintage Chalcolithic

We’ve covered about all there is to say about Ötzi based on his remains, but there is plenty more to discuss. When the iceman was first discovered, he was decked out in a full assortment of clothing, giving us a glimpse into Late Neolithic fashion.

Ötzi was a man who liked his leather and he used skins and hides from at least five different animals to craft his outfit. One of the researchers who helped analyze and recreate his clothing called him “pretty picky” when it came to selecting his materials so it seems that Ötzi may be the earliest-known fashionista in history.

The iceman was wearing a coat, leggings, a loincloth, a cloak, a belt, a cap, and shoes. His loincloth was sheepskin, his leggings were made out of goat hide and his coat was a mixture of both goat and sheep hides that had been stitched together with animal sinew. The coat had been in use for a long time as it had signs of makeshift repairs using grass fibers.

His cloak was made out of woven alpine swamp grass and his hat was a fancy bearskin cap that even had a chinstrap to keep it in place. Whether the cloak was actually a cloak or not is still a matter of debate as too little of it survived to get an idea of its full size and shape. Some have argued that it could have been part of a backpack or simply a mat that the iceman unfurled and slept on.

The belt was made out of calfskin and had another leather strip stitched onto it to make a small pouch which contained several items that we will talk about in a minute. Ötzi also carried a quiver manufactured from the leather of a roe deer.

Image: Otzi shoes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Petr_Hlav%C3%A1%C4%8Dek#/media/File:Replica_of_the_Oetzi_shoes.jpg

An impressive part of the iceman’s outfit were the shoes . They were made out of two layers stitched together. The inner layer consisted of insulating dry grass stuffed into a netting made out of bast fiber string. The outer layer was deer hide, worn with the fur on the inside. A Czech footwear expert who specialized in recreating ancient shoes created replicas of Ötzi’s shoes and gave them to experienced climbers to use them on mountain terrain. They found that the footwear was not only comfortable, but offered great protection and the researcher even got an offer from a Czech company that wanted to buy the rights to sell the shoes.

What’s In The Bag?

To complement his snazzy outfit, Ötzi was also completely kitted out with ancient gear. The highlight of his equipment was a copper axe which is still, to this day, a one-of-a-kind discovery. The haft was approximately 24 inches long, it was made from yew and had a right-angled crook at one end to hold in the blade. That blade was 99.7 percent pure copper, it was fixed into the shaft of the handle with birch tar and tied together with leather straps. This tool saw a lot of action as the blade showed signs of being re-sharpened numerous times.

This was clearly a valuable item and similar axes from around that time period had been found buried with high-ranking men. This led to speculation about Ötzi’s origins. Maybe he had not been just a shepherd or a smelter. Maybe he was someone of high status like a tribe chief. Scientists actually managed to trace the source of the copper and found that it came from southern Tuscany, hundreds of miles from where the iceman was discovered, even though the alpine region had its own copper ore sources. Instead of providing answers, these finds only seemed to deepen the mystery surrounding the Similaun Man.

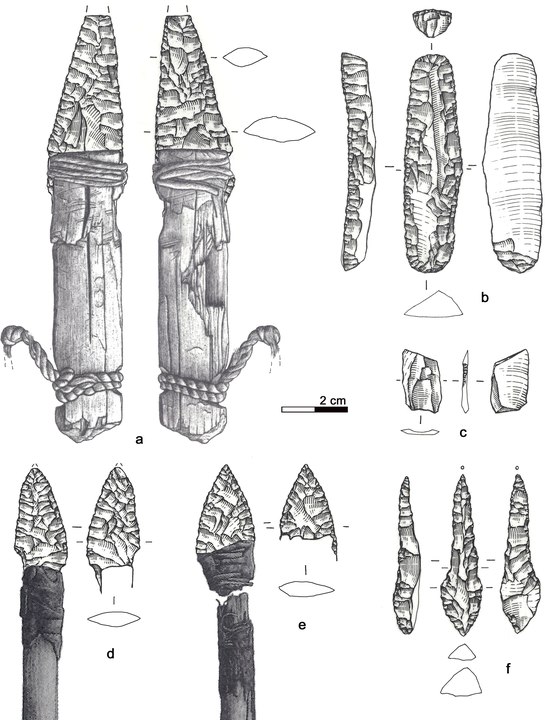

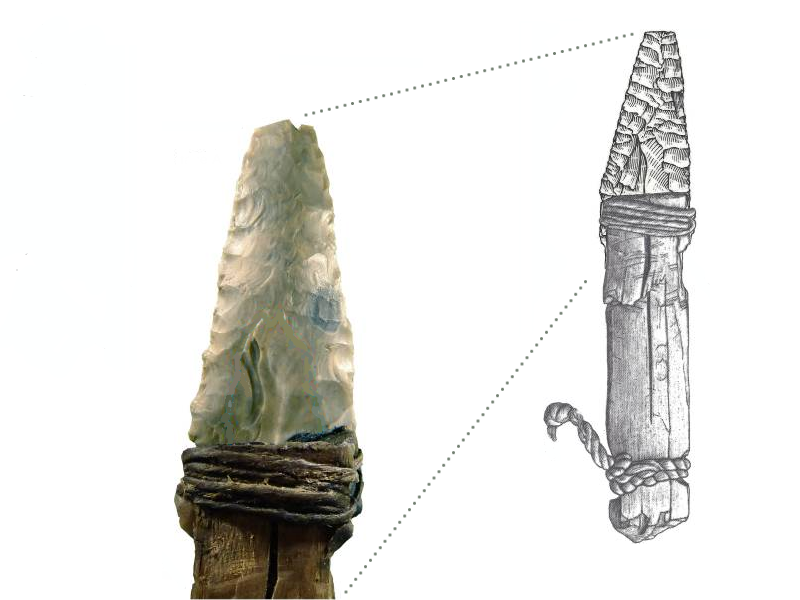

There was plenty more equipment in the iceman’s toolbag. We already mentioned that he had a quiver and it seems he was in the process of assembling a full bow & arrow set. He had a long stave made from yew which he was carving into a functioning bow. He also had 14 arrows made from wayfaring tree and cornelian cherry, although only two of them had been finished with arrowheads and fletching. The quiver also contained a few antler tips and a long piece of bast fiber which would have probably served as the bowstring.

Although not as impressive as the copper axe, but just as unique were Ötzi’s dagger and retoucher. The dagger had a flint blade, an ash wood handle, and a wicker sheath and it still is the only fully-preserved dagger from the Copper Age. The retoucher was a tool that puzzled researchers for a while as they couldn’t figure out its purpose. It looked like a large pencil made from the branch of a lime tree and with a sharpened “core” inside that turned out to be a piece of fire-hardened antler. They eventually realized that the retoucher was used to re-sharpen other tools and weapons, another first for that time period.

Ötzi also had on him two birch-bark containers which held charcoal fragments and various leaves. Given that the insides of one container was blackened, researchers speculate that the iceman used them to carry embers around to start fires.

The rest of the gear included a few pieces of wooden rods and planks which were once part of a backpack, a bird belt used to carry fowl, and two pieces of birch fungus which were threaded onto leather strips, most likely used as medicine.

The Coldest Case

Now we arrive at, perhaps, the biggest puzzle that still surrounds Ötzi – what caused his death? Was he caught in a blizzard? Did he injure himself, thus becoming unable to return to his tribe before freezing to death? Was he a ritual sacrifice? Or was there foul play involved?

For a decade after his discovery, scientists generally believed that Ötzi died of exposure to the elements. It wasn’t until years later that a more advanced CT scan of his remains revealed that the iceman had an arrow wound beneath his left collarbone. Moreover, the shot hit an artery and caused massive blood loss which would have caused Ötzi to go into shock and possibly suffer a heart attack. Even today, the chances of surviving such an attack are around 40 percent, so the iceman had virtually no way of making it out alive.

Investigating his death as a regular cold case, detectives concluded that Ötzi’s assailant got away with murder. Signs pointed to an ambush. Just hours before his death, the iceman enjoyed a heavy meal so he wasn’t in a rush. There were no defense wounds on his body except a cut on his right hand which was a few days old and had already begun to heal at the time of death. As far as motivation goes, investigators ruled out profit because the killer didn’t take Ötzi’s prized copper axe. Despite their conclusions, detectives reluctantly admit that this is one cold case destined to remain unsolved forever.

Someone may have taken out the iceman, but they didn’t take out his bloodline. Believe it or not, Ötzi has descendants still alive today. When scientists sequenced his genome back in 2013, they compared a unique genetic mutation to thousands of samples obtained from donors in Tyrol and found that 19 of them shared the same ancestry as Ötzi. They were all men, as it appears only the paternal line survived.

Who Owns Ötzi?

Controversy seems to have followed Ötzi even in death. We already mentioned that there was a little tiff between Austria and Italy over who owned the remains, but that matter was solved quickly and pales in comparison to the legal dispute between the original discoverers and the Government of South Tyrol.

According to Italian law, Helmut and Erika Simon were entitled to a finder’s fee for locating the iceman equal to 25 percent of his total value. However, the provincial government simply refused to pay this, arguing that they are the ones who covered the expenses of removing and preserving the iceman. In 1994, they offered a measly reward of 10 million lire (€5,200). Unsurprisingly, the Simons refused and went to court. It wasn’t until 2008, 17 years later, that the matter was settled. Although Helmut Simon had died by then, his widow received 150,000 euros.

Simon, who died during a freak blizzard while hiking not far from where the iceman was found, was just one of several bizarre deaths linked to Ötzi, prompting rumors of a curse similar to the one of the pharaohs. Of course, given that hundreds of people were involved in the discovery and study of the frozen man, having a few of them die over the course of decades isn’t that unusual. Even so, the “Curse of the Iceman” just helps add to the mystique that still surrounds Ötzi.