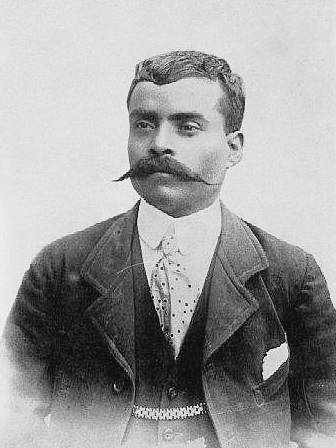

When you hear the words “Mexican Revolution” which historical figure do you immediately picture? We’re guessing it’s Pancho Villa, the sombrero wearing, gun-toting Robin Hood bandit who infamously attacked the town of Columbus, New Mexico in 1916. But while Villa is the revolutionary who gets all the press, he was far from the most respected, most influential, or even most interesting. No. That honor instead goes to a mestizo horse trainer from the impoverished state of Morelos, a man who began his life with almost nothing, and wound up reshaping the whole of Mexico. That revolutionary’s name? Emiliano Zapata.

Born into a small village during the heyday of the Porfirian dictatorship, Zapata’s life should’ve passed in blissful obscurity. Yet a combination of circumstance and timing wound up thrusting him into the spotlight just as Mexico exploded. An uncompromising supporter of land rights for the poor, a general capable of conquering Mexico City, and a tragic folk hero who died for his cause, this is the story of Mexico’s greatest revolutionary.

A Poor Man in a Cruel World

For a man identified so closely with revolution, it’s a mild historical irony that Emiliano Zapata was born just as the greatest period of Mexican upheaval ended.

In 1876, three years before Zapata’s birth, the decades of unrest that had followed independence came to a close when General Porfirio Diaz seized the presidency, ushering in a long period of stability and growth known as the Porfiriato.

But don’t go thinking that stable means popular.

The Porfiriato was a dictatorship. Elections were rigged, dissent was crushed, and the lower classes locked out of power. And nowhere suffered under Diaz’s perfumed boot more than Zapata’s home state of Morelos. In 1879, the year of Zapata’s birth, Morelos was Mexico’s newest state, a small blob of mountainous terrain not 100km from Mexico City. It was also one of the poorest. Seriously, Morelos’s major commodity was dirt-poor peasants farming dirt-poor land.

And this poor quality dirt was about to cause a massive problem.

For generations, the villages in Morelos had relied on communal land to produce enough crops to avoid starvation. But now Porfirio Diaz was in power. And he couldn’t care less about communal land rights. While the Porfiriato turned a blind eye, wealthy land owners known as hacendados started aggressively occupying communal land in Morelos. There’s actually a story – probably apocryphal – that when Emiliano Zapata was just 9 he witnessed his father break down crying after a hacendado fenced off an orchard.

At first, the villages of Morelos tried to fight back.

They petitioned officials, staged protests, even tried to hire lawyers. But the Porfiriato was propped up by the same people stealing that land. What was Porfirio Diaz gonna do? Arrest the hacendados keeping him in power? For Zapata, growing up in Morelos meant growing up in a world where hacendados could not just steal land without consequences, but kill anyone who got in their way.

There’s a famous story about one village lawyer who took his case against a hacendado all the way to Porfirio Diaz himself. Diaz shook the guy’s hand, told him he’d look into it… and then had the lawyer thrown into a labor camp. And that’s where things stood in Morelos just before the Mexican Revolution broke out: a bunch of voiceless, pissed-off peasants desperately crying for a leader to stand up for their rights.

Luckily for them, Emiliano Zapata was about to answer that call.

Stand Up and Fight

So that’s the world Zapata inhabited. But what about the man himself? Who was the guy about to fight for Morelos? Emiliano Zapata was born on August 8, 1879, in the village of Anenecuilco, just one of the many Morelos villages losing vital land to the hacendados.

But while Zapata’s village was dirt poor, the man himself was not. The family Zapata was born into was actually doing kinda OK – at least, by Mexican peasant standards. They had one of the biggest houses in Anenecuilco, and Zapata’s father was a respected horse trainer. This career evidently rubbed off on the young lad. By the time he was a teenager, Zapata was one of the best horse-trainers in Morelos, with even the hacendados after his expertise.

This would turn out to be a very useful trait to have.

Not long after Zapata turned 17, both his parents died. The following year, 1897, Zapata took part in land rights protest and was arrested and drafted into the Porfirian army. But when he was discharged six months later, it wasn’t into poverty.

With Zapata senior dead and Zapata in the army, the super-rich hacendados had become super-desperate for a great horse trainer. And now Zapata was back, they were willing to pay super-big bucks. For Zapata, this was almost like being gifted a bottomless piggybank.

He competed in races, in rodeos; hawked his skills to whoever could afford them.

While he certainly never got rich, he got not-poor. Not-poor enough to afford not just fancy clothes, but also the bucketloads of wax it presumably took to maintain that glorious moustache. As Zapata’s local fame grew, so did his interest in village politics. Remember that possibly-fake story about Zapata watching his father weep over an enclosed orchard?

Well, Zapata certainly seems to have remembered it, because in 1906 he began sitting in on village meetings about how to stop the hacendados being such land-stealing dicks. By 1908, 25% of all land in Morelos was owned by a mere 17 families. Given that the other 75% was mostly low-quality stuff those families didn’t want, this was a serious issue. But Zapata wasn’t yet ready to pick up a gun and fight to make things fairer.

This was 1908. The Porfiriato had stood for 32 years, so long that revolting against it seemed impossible. Yet 1908 was also the year the foundations of the Porfiriato would be destroyed by an unlikely source:

Porfirio Diaz himself.

A Brave New World?

If you’ve ever accidentally blurted out something only to immediately regret it, just know that there’s no way you’ve ever regretted it as much as Porfirio Diaz.

In 1908, Diaz gave an interview to the American journalist James Creelman that was supposed to be full of softball questions Creelman could then write up into a vomit-inducing puff piece. Unfortunately, Creelman just happened to ask what would happen when Diaz – now in his 70s – became too old to run Mexico. It’s here that Diaz didn’t just stick his foot in his mouth, but practically swallowed his own legs.

Diaz declared that Mexico would become a democracy. That he would step down in 1910 and allow a fair election to choose his successor.

“I have waited patiently for the day when the people of the Mexican Republic would be prepared to choose and change their government at every election…” he told Creelman. “I believe that day has come.”

Now this was all highest grade cattle dung. Diaz just wanted to sound good to Creelman’s American readers. But Diaz forgot to tell anyone in Mexico he was lying. So when the interview was published in February, 1908, everyone was like “is this for real?” To which Porfirio Diaz basically replied “Err… yeah? I mean, I guess?”

And so began the slow implosion of the Porfiriato. Down in Morelos, Emiliano Zapata was one of those looking to test Diaz’s word.

The state governor had just died and local elites had put up a jerk to replace him. So Zapata and some other village leaders decided to run their own candidate. If Diaz was for real, he’d let them campaign. And he did. To everyone’s surprise, Zapata and the others were able to travel Morelos, drumming up support for their guy.

This meant Zapata meeting many of the movers and shakers in other villages, and getting his name out across the state, along with his candidate. Come the Morelos election in February, 1909, Zapata’s group were certain they would win.

But, no. At the last moment, Diaz remembered he was meant to be a dictator and rigged the vote. The new Morelos governor lost no time hiking up taxes on the villages that had supported Zapata’s candidate as a warning to never vote against Porfirio Diaz again. To say this made Zapata furious is kind of like saying Krakatoa made a little bit of a bang.

From this point on, he was no longer going to play the Porfiriato’s game.

If Diaz wasn’t going to change by his own accord, maybe it was time someone forced him. The following year, 1910, Zapata made his first stand. A local hacendado had fenced off a communal hillside. So Zapata armed 80 men, went up to that hillside, and tore the fences down. For his trouble, he got labeled a bandit and had to flee into the mountains.

So far, so unimpressive.

But something was about to happen in wider Mexico that would change Zapata’s fortunes. While those in Morelos had gotten early warning that Diaz wasn’t really gonna allow fair elections, the rest of Mexico hadn’t got the message. So come the 1910 election, a wealthy liberal named Francisco Madero ran against Diaz. And – crucially – everyone decided to vote for him.

And suddenly Diaz was faced with a country full of people desperate to see the back of him.

Of course, Diaz didn’t let the vote happen. True to type, he had Madero arrested and declared himself winner of a new presidential term. But Diaz had unleashed a very powerful genie with the Creelman interview, a genie called Hope. And, once that particular genie was out the bottle, it proved impossible to put back.

Later that year, sympathizers helped Francisco Madero escape Mexico and get into the US.

There, Madero made a momentous decision. If Diaz wasn’t going to leave voluntarily, Madero would force him out at gunpoint.

Viva la revolución!

Today, Mexico celebrates November 20 as a public holiday, as that’s when Madero declared his revolution against Diaz. But if you’d been in Mexico on November 20, 1910, you’d have barely noticed.

That’s because Madero’s call to arms was heeded by no-one.

Well, almost no-one. The only reason November 20 has gone down in history is because one of the few people to heed Madero’s call was Pancho Villa. And Villa was a guy who knew how to do revolution. But what about Zapata? How did he respond to Madero’s call?

Um, he didn’t really do anything.

Down in Morelos, Zapata couldn’t give a cat’s gonad what Pancho Villa was doing way up in the north. Sure, he wanted Diaz gone, but it’s not like Madero was promising land reform. In early 1911, though, things changed. On March 11, Madero crossed back into Mexico to take control of the growing revolutionary army. Almost immediately, they started whupping Diaz’s guys in battle. Zapata now faced an urgent choice. Either jump onto this revolutionary bandwagon and hope things worked out, or step back from the brink and wait for the next opportunity.

Zapata jumped.

That May, Zapata’s peasant army managed to capture the city of Cuautla. At the same time, Pancho Villa seized Ciudad Juárez. Faced with multiple revolutionary armies on multiple fronts, Diaz saw the writing on the wall. On May 25, 1911, Porfirio Diaz resigned and boarded a boat to Europe. He would die in exile just four years later.

Fair warning: Diaz is just about the only person in this video who isn’t going to die violently. In the wake of Diaz’s flight, an interim president took over for the sole purpose of organizing new elections. Since everyone knew Madero would win, the interim president asked the revolutionary armies to stand down. To which Zapata replied “nah, we’re good,” and promptly captured Cuernavaca. If that seems strange to you, just remember that Zapata had been burned before. He wasn’t going to end his rebellion until Madero had committed to land reform.

That June, the two men finally met in Mexico City to discuss the issue.

While Madero didn’t give any firm commitments, Zapata did leave the meeting thinking Madero was an honest man he could do business with. He was so convinced of this that even when the federal army attacked Morelos under the bloodthirsty General Victoriano Huerta, Zapata thought it was all the interim president’s fault. That Madero would put an end to all this when he was finally elected.

Oh, Zapata. Are you in for a nasty surprise.

That October, 1911, Madero won the presidency in a landslide. Almost immediately he dispatched an agent to negotiate with Zapata. At first, things went well. The agent seemed super into Zapata’s ideas on land reform, and it really looked like things were going somewhere.

And then it all went wrong.

Either acting under secret orders or because he’d gone rouge, a general in the federal army surrounded Zapata’s men in the middle of negotiations. When Zapata tried to desperately contact Madero, he got an odd message back. We will negotiate, Madero assured him. But only if you surrender unconditionally.

It was the last straw.

Zapata broke off negotiations. Taking a small band of men, he fled back into the Morelos mountains, bitter at his apparent betrayal. It was clearly time for another revolution.

Only, this time, it would be Zapata leading the charge.

The Plan of Ayala

At this point you may be wondering why Zapata is a guy who deserves a Biographics. Sure, he’s helped overthrow one dictator, but there’s gotta be more, right? Well, yeah, there is. And it’s known as the Plan of Ayala. Issued by Zapata on November 28, 1911 – barely three weeks after Madero double-crossed him – the Plan of Ayala is still one of history’s key revolutionary texts. A radical agrarian manifesto, it would go on to influence nearly every Latin American revolutionary since. And, boy, are there ever a lot of Latin American revolutionaries.

So what was it?

At its heart, the Plan of Ayala was a vision for a fairer world based on land redistribution. While it comprised of 15 points, most of them were just trash talking Madero, so we’ll concentrate strictly on points 6 through 8. In abridged form, they went something like this:

Point 6: communal land seized by hacendados will be given back to villages.

Point 7: One third of all land held by the rich will be expropriated and given to the poor, so everyone has a chance to improve their lot in life. Landowners will be compensated.

Point 8: Those who resist point 7 will have their lands nationalized without compensation, with the government using this land to create a fund for war widows and the very poorest.

The Plan of Ayala wasn’t so much a game changer as it was the creation of a whole new game. At the time it was written, the Russian Revolution was still several years off. The idea of a revolt that put the very poorest in society at its heart was near unprecedented. This was a radical, radical document.

And it was going to blow up Mexico.

That winter, revolts against the Madero government inspired by the Plan broke out across Mexico. So the government fought fire with fire. In Morelos, the federal army took Zapata’s family hostage. Started burning down villages and funneling the survivors into concentration camps. Zapata himself couldn’t have run a better recruitment campaign. As the atrocities mounted, his ranks of guerilla fighters swelled to the tens of thousands.

Not that Zapata ran anything like a regular army.

His soldiers were peasants. They often took up arms when needed, only to put them down again the moment the battle was won and go back to farming. Nor was Zapata actually their leader yet. At first the peasants in Morelos fought in small, decentralized groups who occasionally came together to take a city or whatever.

It wasn’t until early 1913 that Zapata could really be said to be in charge.

And by then, his Zapatista army was on the verge of taking Mexico City. When he issued the Plan of Ayala, Zapata had also issued a promise to march into Mexico City and personally hang Madero from a tree. Come early 1913, it really looked like he was gonna do it.

But fate had other ideas.

On February 9, an attempted coup broke out in Mexico City, led by Porfirio Diaz’s nephew, Felix Diaz. While Madero managed to hunker down safely in the Presidential Palace, he also couldn’t defeat the insurrectionists. So he called in General Huerta, the guy we last met killing civilians in Morelos. Huerta took one look at the mounting death toll and decided he could use this for his own ends.

On February 17, Huerta switched sides. Backed by the US ambassador, he convinced Madero to surrender. Then he had Madero loaded into a car, driven to a secluded spot, and shot dead. In the aftermath of the Ten Tragic Days, Huerta sidelined Felix Diaz and had himself declared president. His first act was to send a messenger to Zapata and see if he wanted to join forces.

It was the beginning of a new era in the Mexican Revolution. And it wouldn’t end until nearly all its players were dead.

We Almost Won…

The dictatorship of General Huerta was as short and as pointless as a blow-up Napoleon sex doll. When Zapata got Huerta’s offer to join forces he was all like “wait, weren’t you the guy killing all those villagers in Morelos? Uh, NO,” and went straight back to fighting.

But Huerta was also unpopular outside Zapata’s clique.

In the North, Pancho Villa restarted his revolution. In the state of Coahuila, governor Venustiano Carranza declared himself in rebellion and raised an army known as the Constitutionalists. Before Huerta could even warm the president’s chair, his regime was crumbling on all sides. It didn’t help that Huerta was basically trying to be the new Porfirio Diaz. Even those who supported his coup didn’t want to live under a Porfiriato tribute act.

By mid-1914, the combined pressure of the Zapatistas, Pancho Villa’s army, and Carranza’s Constitutionalists had left Huerta a dictator incapable of dictating to anyone. On 14 July, Huerta resigned and fled Mexico. Although he would later try to re-enter the country and raise a new army, he’d be arrested at the border by US authorities. He died in prison in 1916.

But while Huerta’s departure was a win for the revolutionaries, it also made things a thousand times worse.

The problem was that Zapata, Villa, and Carranza were all in this fight for different reasons. Zapata wanted land reform and to Hell with everything else. Villa wanted money and fame and to hang some elites, while Carranza wanted to be president without quite knowing why.

When Huerta fled, all three of them started eyeing one another sideways, like the three cowboys at the end of The Good the Bad and the Ugly, knowing they’re going to have to draw pistols on one another, but unsure until the last second who they’re going to shoot. Zapata finally made his decision in the fall. After a failed October meeting between the three revolutionary armies in Aguascalientes, Zapata got frustrated and ordered his men to march on Mexico City.

On November 24, Carranza fled the city ahead of 25,000 armed Zapatistas.

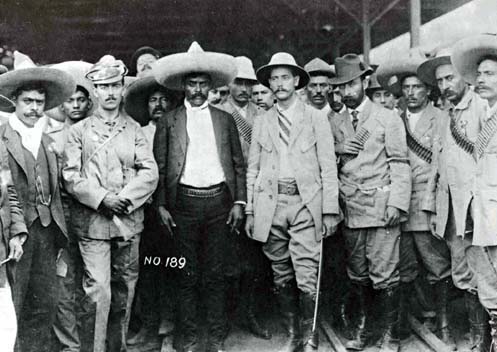

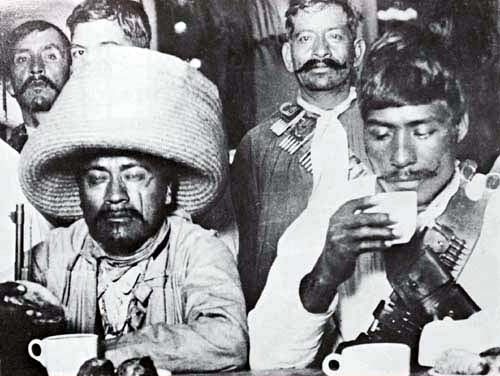

Incidentally, those Zapatistas were all so overwhelmed by the capital that instead of raiding it they went barefoot from door to door, shyly asking for food and water. But Zapata hadn’t taken the city to show off. He was here to do business. On December 6, that business finally arrived.

Pancho Villa rode into Mexico City at the head of an even bigger army than Zapata’s. The two men met at the Presidential Palace to work out the basis of an alliance. The basis was this: they would both work to lock Carranza out of power. In return, Zapata would get his land reform, while Villa would get a civilian president – one whose name likely rhymed with “Bancho Billa.”

As these two great revolutionaries left the palace, they must’ve felt their time had finally come. That they were unstoppable. Neither man knew that the high water mark of the revolution had already come and gone.

All that was left now was for the two of them to be swallowed by the waves.

The Plan in Action

Not long after his meeting with Villa, Zapata abandoned Mexico City. Back in Morelos, he started putting the Plan of Ayala into action. In practice, this meant redistributing land however he saw fit. Mostly that involved expropriating haciendas, but Zapata wasn’t above burning them to the ground if the local hacendado refused to comply.

The Zapatistas even set up a Rural Loan Bank, helping peasants buy their own plots to farm.

It was a transformation for Morelos, one that Zapata was sure would provide a template for the entire country. He even contacted Woodrow Wilson’s White House to see if they fancied recognizing him as Mexico’s legitimate president.

The White House passed on the offer. But whatever high Zapata was feeling in early 1915 was about to be lost forever. As was his newest ally.

In April, Pancho Villa fought Carranza’s forces at the Battle of Celaya. Villa used his classic near-suicidal cavalry charge, which in this case turned out to be completely suicidal. Carranza’s general, Álvaro Obregón, had been studying tactics from WWI, and used machineguns to mow down Villa’s army.

By the end of the battle, Villa was alive but no longer a threat.

That meant there was nothing to stop Carranza from turning his attention solely onto Zapata. That October, the United States officially recognized Carranza as Mexico’s head of state. Around the same time, the federal army moved into Morelos, determined to bring Zapata to heel.

Once again, villages were burned. Once again, civilians were killed.

But this time, Zapata didn’t just flee to the hills as a noble folk hero. He tried to fight back using Carranza’s own tactics. The results left indelible bloodstains on Zapata’s legacy. In November, 1916, Zapatistas bombed two passenger trains heading into Mexico City. The terror attack killed almost 400 people – double the death toll of the 2004 Madrid Train Bombings.

While the slaughter didn’t dent Zapata’s popularity in Morelos, it left him isolated in the rest of Mexican society. The final nail in the coffin came in early 1917. After months of deliberation, Carranza promulgated a new constitution that basically ripped off the Plan of Ayala.

It opened the door for expropriations. For nationalization of communal land. For redistribution. For a fairer society where peasants were actually treated as human. For most Mexicans, the Constitution of 1917 made Zapata’s fight seem pretty pointless. “Dude, you’ve already won. Just stop fighting!”

But Zapata wouldn’t stop. Or maybe couldn’t.

And, realistically, who could make him?

He was still popular in Morelos. No matter how many trains Zapata bombed, no matter how constitutions Carranza issued, nothing would change the fact that Morelos was going to stand by Zapata to the bitter end. So Carranza simply made sure that end came quicker and was more bitter than anyone had expected. In 1919, a federal general fighting in Morelos named Jesús Guajardo abruptly switched sides. His unit turned on the other federal forces, killing 59.

When he got the news, Zapata arranged a meeting with Guajardo, eager to bring him into the Zapatista fold. Guajardo suggested they meet at a remote hacienda. Apparently having never heard of the concept of a trap, Zapata agreed. On April 10, 1919, Emiliano Zapata and ten armed men rode to the abandoned hacienda to negotiate with Guajardo.

Before Zapata could even open his mouth, dozens and dozens of federal soldiers opened fire from hiding places. The revolutionary never stood a chance. Zapata died that day in a hail of bullets, just the latest Mexican revolutionary to meet a violent fate.

He wouldn’t be the last.

Barely a year later, on May 21, Venustiano Carranza would be assassinated in turn by his former general, Álvaro Obregón. Obregón’s luck would last a little longer, before he, too, was assassinated in 1928. By then, the only other leader to survive the revolution was also dead. Pancho Villa was gunned down in 1923, in an ambush not unlike the one that killed Zapata. And, just to tie things up, we should probably mention that Guajardo was also assassinated after helping arrange Zapata’s assassination, because apparently that’s just how things roll in revolutionary Mexico.

Hey, we did warn you everyone in this video but Diaz was gonna die violently.

At the end of all that bloodshed, then what did Emiliano Zapata achieve? Why do we still know his name today? For an answer to that, just look back at the Plan of Ayala. In the decade of the revolution, land reform had gone from a drum being banged by a few obsessed peasants in Morelos to something the whole of Mexico cared about.

Even though Carranza’s 1917 constitution was scrapped after his assassination, elements of the Plan of Ayala still crept into its successor. Even today, it affects how many in Latin America think about land rights. But Zapata was more than just a guy who wrote an influential plan.

In his years as a revolutionary, Zapata became famous as someone who cared about the poor, who was uncompromising in his beliefs, who was willing to stand up to a rotten system. He was far from a perfect man, but he was also something more than a mere human. He was a folk hero, a Robin Hood who really existed. A myth brought to life.

For all his faults, Emiliano Zapata is one folk hero the world will never forget.

Sources

Excellent podcast on Zapata’s early life (multiple episodes): https://www.revolutionspodcast.com/2018/09/907-morelos.html

Episode two: https://www.revolutionspodcast.com/2018/11/913-the-plan-of-ayala.html

BBC Podcast on the Mexican Revolution: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00xhz8d

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Emiliano-Zapata

Biography: https://www.biography.com/political-figure/emiliano-zapata

Francisco Madero: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Francisco-Madero

Huerta: https://www.thoughtco.com/biography-of-victoriano-huerta-2136491

Carranza: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Venustiano-Carranza

Mexican Revolution: https://www.britannica.com/place/Mexico/The-age-of-Porfirio-Diaz

Mexican Revolution: https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/mexican-revolution-and-the-united-states/civil-war-conventionist-view.html

Read the Creelman interview here: https://library.brown.edu/create/modernlatinamerica/chapters/chapter-3-mexico/primary-documents-with-accompanying-discussion-questions/document-4-president-diaz-hero-of-the-americas-by-james-creelman-1908-interview-with-president-porfirio-diaz/