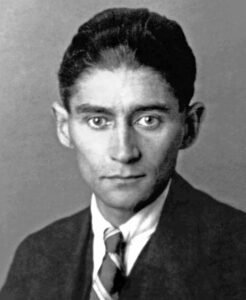

One hundred years ago, a reclusive Czech-Jew living anonymously amid Prague’s spires managed to change the way we see the world. He was the son of a shopkeeper, an insurance lawyer by trade. Outwardly, he appeared sickly, forgettable. But inside? Inside, this sallow young man’s mind was alive: with visions of horror, with paranoia, existential dread, and alienation. Working at night, he took those visions and etched them onto paper, creating fiction unlike anything ever seen before.

That young man’s name was Franz Kafka. And his work would shape the entire 20th Century.

Born into a German-speaking family in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Kafka spent his whole life suffering from illness and anxiety. He was miserable at home, unlucky in love, and too depressed to function anywhere but in his insurance office. Yet he made up for this by having a mind so strange, so inventive that today he’s arguably Europe’s most famous author. Join us as we delve inside the work of Franz Kafka, and the awful life that made it all possible.

Early Years: In the Penal Colony

It was a hot July day in 1883 when Hermann Kafka became a father for the first time. A Prague shopkeeper from a working class Jewish family, Hermann was a man who’d fought all his life to get where he was. His battle had been a tough one. 1883 was the era of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, when Prague was dominated by Germans, and Jews were at a constant disadvantage.

Through the sheer force of his gigantic, volatile personality, Hermann had managed to take a little clothing shop and turn it into a bustling store. He’d bought a fancy house, found an educated wife, even broken into the closed world of the German elites. And now his first son had arrived. The son who was going to be as sporty, as commanding, as powerful, and as straightforwardly Germanic as his old man affected to be. It’s likely that, as Hermann took baby Franz Kafka into his arms for the first time, he felt a rush of pride.

If he did, it was the last time he ever felt anything but contempt for his son. From the earliest age, it was obvious that Franz Kafka was not the stout, hearty man Hermann wanted him to be. The boy was small, sickly. He was troubled by boils, and afflicted with melancholy. From Hermann’s perspective, this was a little like opening a box you think is going to contain a delicious cake, only to discover it instead contains bitter disappointment.

But from Franz Kafka’s perspective, it was like being born into a world where everything you did was doomed to end in humiliation. Hermann was an angry man at the best of times, but something about his ineffectual son seems to have actively offended him. He would explode at young Kafka for no reason. Belittle him endlessly for being useless, pathetic, a failure of a human.

Perhaps its not surprising that, by the time Kafka started school, his self-esteem was in the gutter.

Still, while he may have done everything in his power to destroy his son’s confidence at home, Hermann was still, at heart, a social climber. That meant making sure that, outwardly, Kafka appeared to have every advantage in life. As Hermann’s business boomed, he began sending Kafka to the elite Altstädter Staatsgymnasium, having one of the family’s Czech servants walk the lad there every morning. For the working class Jew, it must’ve been a whole peacock’s worth of feathers in his cap to send his boy somewhere so prestigious.

But for his shy, miserable son, it was simply Hell. Kafka hated the school. Absolutely hated it. While he did well academically, he found the place authoritarian, dehumanizing, alienating.

It was around this time that a black parasite first began to tunnel its way into the boy’s brain. That parasite was what we’d today call a serious anxiety disorder. One that made Kafka constantly feel like there was a ball of wire at the center of his body, winding ever tighter. If you’ve ever suffered from anxiety, you’ll know that “suffering” is the exact right term to use. Well Franz Kafka would suffer from it for the rest of his life.

However, the boy’s teenage years weren’t all bad news.

Between the emotional abuse at home and his miserable life at school, Kafka needed an outlet, somewhere he could escape to. A warm burrow he could hide in. It was at this time that the boy started writing.

Description of a Struggle

Come 1902, Franz Kafka was studying law at Charles University, and writing on the side. He’d actually wanted to study chemistry, but had switched to law after two weeks when Hermann pressured him, because law would look better to the family’s middle class friends. And with his son already a self-declared atheist and socialist, Hermann desperately needed a new feather for his suddenly bedraggled-looking cap.

Yet even with his father still controlling his life at university, Kafka managed to eke out some space for himself. He joined Lese und Redehalle der Deutschen Studenten, a literary club for German speakers. While at this club, he met the man who would one day come to define Kafka’s legacy.

That man was Max Brod.

Born about a year after Kafka, Max Brod was an outgoing Jewish intellectual who was charming, creative, intelligent, and everything Kafka felt he himself was not. Nonetheless, the two hit it off, forming their own little clique. It would be this close friendship that later saved Kafka’s writing from the ashes.

But not yet. Brod and Kafka were both just students at this time, a long way from actually publishing their stories. So when Kafka finally graduated in June, 1906, it was not into a life of writing and plumbing the depths of the human soul, but into a life of working as an unpaid clerk for the local courts. To say Kafka found this job crushingly dull would be to overestimate how exciting it was.

The work left him cranky, depressed, and lethargic. Worse, he was still living at home, still dealing with Hermann’s volcanic temper and tiny cruelties. His only solace was that soon it would be over. Soon, Kafka would have enough experience to join an international office, one that would send him abroad, away from his father.

In October, 1907, Kafka finally signed up with an Italian insurance company, fully expecting to be sent down to Italy at any day. Instead, he found himself stuck in a Prague office, dealing with suffocating bureaucracy, unpaid overtime, and brutal hours that left him too exhausted to write.

By the time Kafka finally resigned, his dream of living abroad had been crushed. Instead, he meekly resigned himself to staying at home, to living in Prague and sharing a house with Hermann, to living with his father’s constant putdowns. In August, 1908, Kafka began his new job at the Worker’s Accident Insurance Institute in the shadow of Prague Castle.

He would stay there for the rest of his working life. But even as Kafka’s dream of leaving his abuser far behind faded into distant memory, he began to nurture another. Kafka’s new job finished in the mid-afternoon. If he slept after it finished, that meant he could wake up after dark and spend most of the night writing.

Kafka would later say this routine felt less like a calling or a hobby than a form of communion. Maybe even a penance, with writing being the only way he could atone for the sins he was convinced filled his stick-thin body.

That same year, Max Brod convinced Kafka to publish his first stories. Although they sold poorly, the critical reaction was good enough to convince Kafka to keep writing.

The Metamorphosis

In August, 1912, Kafka arrived at a dinner party in Max Brod’s home to find his friend had an unexpected guest. It was now four years since Kafka had published his first collection of stories, and he was waist deep in the novel that would later become Amerika, AKA The Man Who Disappeared. But that night, literature was the furthest thing from Kafka’s mind.

He was too busy thinking about the woman sat opposite him. Felice Bauer was one of those “friends of a friend of a cousin” types that the gregarious Brod would invite to his home, a woman who usually lived in Berlin but was visiting Prague. In his diary, Kafka would later write that she had a:

“bony, empty face that wore its emptiness openly. Bare throat. A blouse thrown on… Almost broken nose. Blonde, somewhat straight, unattractive hair, strong chin. As I was taking my seat I looked at her closely for the first time, by the time I was seated I already had an unshakeable opinion.”

That unshakeable opinion was that he was in love.

This being Franz Kafka, the courtship that started that summer evening wasn’t exactly conventional. He waited until Felice Bauer had gone back to Berlin before telling her of his feelings via letter. From then on, the two were writing to one another two times a day. Or Kafka was, at any rate. For her part, Bauer seems to have been flattered, but maybe not quite to the extent of writing long, heart-rending letters every few hours.

Still, her effect on the writer was palpable.

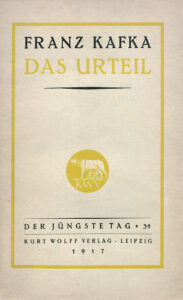

Not six weeks after they’d met, Kafka sat down one evening at his desk overlooking the Vltava River. By the time he got up again, it was dawn, his legs were in agony, and he’d just finished his first masterpiece. The Judgement is a hard tale to describe, in that it’s a typically Kafka short story without an easy meaning.

The basic plot is that a young man goes to tend to his sick father. But as the tale progresses, the father grows in stature and power until, like some terrible, tyrant king, he rises from his bed and condemns the young man to death by drowning. The man immediately goes and throws himself into the Vltava.

Gee, we wonder where your son got the inspiration for that tale, Hermann.

Yet if the tale sounds slight in our description, actually reading it is a whole other experience. The tale is darkly humorous, almost allegorical, but at the same time shot through with a sense of grander themes lurking beneath the surface, just out of reach. For Kafka, it was the first good thing he ever wrote, the moment when he metamorphosed from a man who did some writing to an actual writer.

That same year, he would sit down and write a much more literal tale of metamorphosis, about Gregor Samsa, who woke up one morning from uneasy dreams to find himself changed in his bed into a monstrous vermin. But while The Metamorphosis would be the only work in Kafka’s lifetime that sold well, and would remain his best-known story, it was The Judgement that the author considered his masterpiece.

At the top of the first page, he scrawled a hasty dedication.

“To Miss Felice Bauer.”

A Little Woman

When you look at this period of Franz Kafka’s life, it’s remarkable just how closely his work parallels his relationship with Bauer. Remarkable, because the two barely ever met. Although they constantly sent one another letters, Kafka constantly turned down chances to meet his “beloved” in the flesh. He was too busy at work. His writing required attention. He had a headache and was washing his hair.

It’s been suggested the paradox at the heart of Kafka’s life is that he thought he wanted to be left completely alone, but secretly craved human contact. Or maybe the other way around. Still, he evidently longed for company enough to eventually propose to Bauer. By letter, naturally. On May 31, 1914, the couple finally met face to face again at their engagement party. Surrounded by his family and Felice’s, Kafka felt nothing but bottomless misery.

Before three months were out, the two had mutually broken off their engagement. Although they’d wind up getting back together, you can see clearly the effect this rollercoaster had on Kafka’s work. 1914 was the year he abandoned Amerika with just one chapter left to write.

It’s the year he wrote In the Penal Colony, a grim, cruel story that’s even darker than The Judgement.

It’s also the year he started his most famous novel of all: The Trial. The story of a man, Joseph K, who is charged with a crime without ever knowing what that crime is, The Trial is a landmark of absurd, alienated fiction. For chapter after chapter, Joseph K tries desperately to find out what he’s guilty of, while uncovering all sorts of bizarre figures, grotesque tortures, and strange sexualized rituals happening in secret rooms. By the end, we still don’t know what crime he committed.

Because it’s so ambiguous, The Trial has come to symbolize a million things to a million readers. For some, Joseph K’s crime is simply that he’s human. For others, it’s that he’s a Jew living in an anti-Semitic world. Others see in it a premonition of the Soviet Union’s secret police. In the 1960s, Orson Welles made a film version that hinted Joseph K was targeted for being gay.

In short, The Trial is one of those books that’s so universal everyone can see their experiences reflected in it. But not during Kafka’s lifetime.

In 1915, the reclusive writer slipped his manuscript of The Trial into a desk drawer. He never looked at it again. The following year, Kafka and Felice Bauer spent nearly two weeks in the spa town of Marienbad, attempting to patch things up. It worked and, on July 12, 1917, the two got engaged all over again. This time they even started making plans to live together in Prague.

But 1917 was also the year Franz Kafka got some life changing news. Or maybe life ending might be more accurate. That year, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis.

In the early years of the 20th Century, tuberculosis was a death sentence. The disease killed Andrew Jackson, Jane Austen, George Orwell, and was once estimated to have killed 15% of all people who had ever lived. And it would kill Franz Kafka too.

In December, 1917, a sick and depressed Kafka broke off his engagement to Felice for a second time. For Felice, this was the last straw. She cut off contact with her former fiancee, found a more stable man to marry. The part of Kafka that wished he could be completely alone had gotten what it wanted.

Kafka’s Judgement

On October 28, 1918, the Austro-Hungarian Empire gave one last groan and collapsed. As WWI drew to a close, Prague found itself no longer under Germanic rule, but part of a new republic composed of Czechs and Slovaks. At his workplace, Kafka was taken for questioning along with all the other German speakers to see if they supported the new regime. Those who were actively against it were fired.

But we can only imagine that Kafka didn’t care all that much about that stuff. He had more important things to worry about. In early 1919, Kafka was taking some time away from Prague in a boarding house when he happened to meet Julie Wohryzek. At only 28, she was nearly 8 years his junior. But still, the two fell to talking, and bonded over a shared love of Yiddish theatre and risque humor.

By the time they both returned to Prague, Kafka had decided to marry her. As firm bases for a lasting relationship go, there are probably better ones. But still, Wohryzek agreed, and an excited Kafka ran to tell his parents. At which point Hermann Kafka detonated like a pink, flabby bomb. If Hermann disapproved of his useless son in general, then you’d have to invent whole new ways of measuring disapproval to understand how he felt about this whirlwind marriage.

For the next few months, Kafka’s father harangued him. Bullied him. Browbeat him over his plans. At first, Kafka tried to stand his ground. But a lifetime of belittling had crushed his self esteem down to nothing. In November, 1919, Kafka broke off his engagement with Wohryzek.

Not long after, Kafka left Prague again and checked himself into the same guesthouse where he’d met his second fiancee. There, he sat down and composed a letter to his father, finally saying all the things he was too scared to say to his face. Running at 45 pages, Kafka’s Letter to His Father was his own judgement on the tyrant who’d raised him.

What’s remarkable today is just how clear-eyed it was.

Kafka was at pains to stress he understood his father’s position; that he knew dragging yourself up from a working class background was not an easy thing to do. While Hermann may be the villain in our story today, it’s worth remembering that no-one in real life is purely evil. Hermann Kafka was just a man who’d been taught by the snobbish society he lived in that only being loud, brash, and angry would get him noticed, get him respected.

It’s just a shame he felt those qualities should apply to his parenting, too. At the end of the letter, Kafka wrote that he hoped his honesty would open the door to an improved relationship between the two of them. But then, shy and insecure to the last, he chickened out of posting it.

The next year, possibly as a rebound, Kafka started a relationship with one of his translators in Vienna, a Czech girl called Milena Jesenska. But when November again rolled around, Kafka abruptly broke off the relationship.

Once again, the twisted version of Hermann sitting in the center of Kafka’s mind had condemned the writer to a living death.

A Hunger Artist

Kurt Vonnegut once wrote that Kafka’s stories exemplify a certain type of fiction, in which the protagonist starts miserable, only to see things get continuously worse. The same was true of Kafka’s life. Fair warning: there’s going to be no heroic moment in this tale. No emotional climax where Kafka manages to finally stand up to Hermann, get the girl, and ride off into the Prague sunset.

No, instead, we’re going to watch a miserable man’s life get continuously worse, until it all ends the only way it can. By 1922, it was obvious what that ending would be. That year, Kafka’s tuberculosis got so bad he was finally forced to retire from work.

In one sense, this was actually a good thing. Kafka had long wished he could devote himself to writing full time, and now there was nothing stopping him. That January, he began writing his last great work, The Castle. The story of a man known only as K, The Castle follows K’s attempts to meet the authorities presiding over a snowbound town, only to discover his path blocked at every turn.

Today, The Castle is seen as Kafka’s most mature novel. But Kafka himself didn’t feel this way. On September 11, 1922, Kafka wrote to Max Brod to inform him he’d given up on the story and would never return to it. Yet it wouldn’t be fair to say Kafka had also given up on life.

The next year, the sick man moved to Berlin. One day, he booked himself a trip to the resort town of Muritz to try and help his TB. It was while on the shore that Kafka met Dora Diamant. A 19-year old socialist, Dora was 20 years Kafka’s junior. But she was also fiercely intelligent, with hard-edged political beliefs, and a passionate support for Zionism that chimed with Kafka’s own feelings.

At Muritz, the two talked and talked until, finally, it seemed only natural that Dora would return to Berlin with Kafka. But don’t assume this was some great autumn romance.

By 1923, Kafka was so sick that Dora’s role was more that of a live-in nurse than a lover. He was also stony broke. Hyperinflation had gripped Weimar Germany, wiping out Kafka’s pension. By November, 1923, the pair were reduced to using candles to heat their food. Still, Dora’s influence was causing Kafka to feel a tiny ray of optimism for the first time in years.

He even began making plans to move to Palestine.

But this is the story of Franz Kafka. And there was no way fate was going to grant him such happiness. In early 1924, Kafka’s health finally collapsed. Forced by his doctor to check into a hospital, Kafka selected a sanitorium outside Vienna. Then, gloomily, he left Berlin for good. As he made his way towards his final resting place, Kafka found time to stop in Prague. Just long enough to give Max Brod his unfinished manuscripts of The Trial, Amerika, and The Castle and ask him to burn them.

In late March, 1924, Kafka arrived at the Vienna sanitorium for treatment. Three months later, on June 3, he died of his illness. On his deathbed, he wried Dora Diamant’s father, asking for permission to marry her. Dora’s father curtly replied “no.” At the time he passed away, Kafka was a man whose life story seemed to be that of a sickly insurance lawyer who was unlucky in love, and never did anything of note.

His writing was known only by a tiny circle of Prague intellectuals, and even they’d only seen the published stuff. The bulk of his work had been seen only by Kafka, who died having made his best friend promise to burn it all.

Luckily for posterity, that best friend just happened to be a consummate liar.

The Man Who Re-Appeared

Many years later, Max Brod would reflect on his final meeting with Kafka, and offer this explanation. According to Brod, Kafka knew his best friend would never burn his manuscripts. If he’d really wanted them destroyed, he would’ve asked Dora or Hermann, who’d have probably burned them with relish. By asking Brod, Kafka was in effect asking the one person he knew would ignore his wishes and try to publish his novels.

And that’s exactly what Brod did.

All through the rest of 1924, Brod diligently organized Kafka’s papers, sifting the piles of notes into chapters, grouping them by theme, figuring out how they might slot into a wider novel. By early 1925, he was finished. That April, Brod used his literary connections to get The Trial published. It was well enough received in Europe that The Castle followed a year later, and Amerika a year after that.

By 1930, all three of Kafka’s novels, plus his collected short stories, were available for European intellectuals to marvel over. Come 1937, the first English editions even began to appear. But it would be another decade before the spark really lit. After WWII, publishing houses in America began to take a chance on this long-dead author they were hearing so much about.

It was this more than anything that cemented Kafka’s reputation.

For whatever reason, postwar America was primed and ready for Kafka. His popularity exploded. People like Nabokov sang his praises. Below the border, southern American writers like Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Jorge Luis Borges devoured his works. The rest, as they say, is history. Today, Kafka is one of a handful of writers almost everyone has heard of, an author as recognizable as George Orwell, Edgar Allen Poe, or H.P. Lovecraft.

But while all these men were known as writers in their day – even the underappreciated Lovecraft – Kafka is maybe the only one who rose from complete obscurity, and brought such complex, unique riches with him. If you go to Prague’s new Jewish cemetery today, you can still see the shared grave where Kafka and Hermann lie for eternity, side by side.

But while Kafka may not have been able to escape his abusive father even in death, he has now escaped Hermann’s judgement. Because history remembers him not as a disappointment, but as Franz Kafka: the writer who changed the way we see the world.

Sources

Highly-detailed bio (via the Kafka Museum in Prague): https://kafkamuseum.cz/en/franz-kafka/educational-career/early-childhood/

https://www.biography.com/writer/franz-kafka

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Franz-Kafka/Works

http://www.kafka.org/index.php?biography

Max Brod: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Max-Brod

Kafka and Felice Bauer: https://lithub.com/kafka-was-a-terrible-boyfriend/

Meeting Felice: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/jan/15/john-banville-kafka-trial-rereading

The Judgement: https://www.thoughtco.com/judgment-study-guide-2207795

Letter to his father (some extracts): https://www.brainpickings.org/2015/03/05/franz-kafka-letter-father/