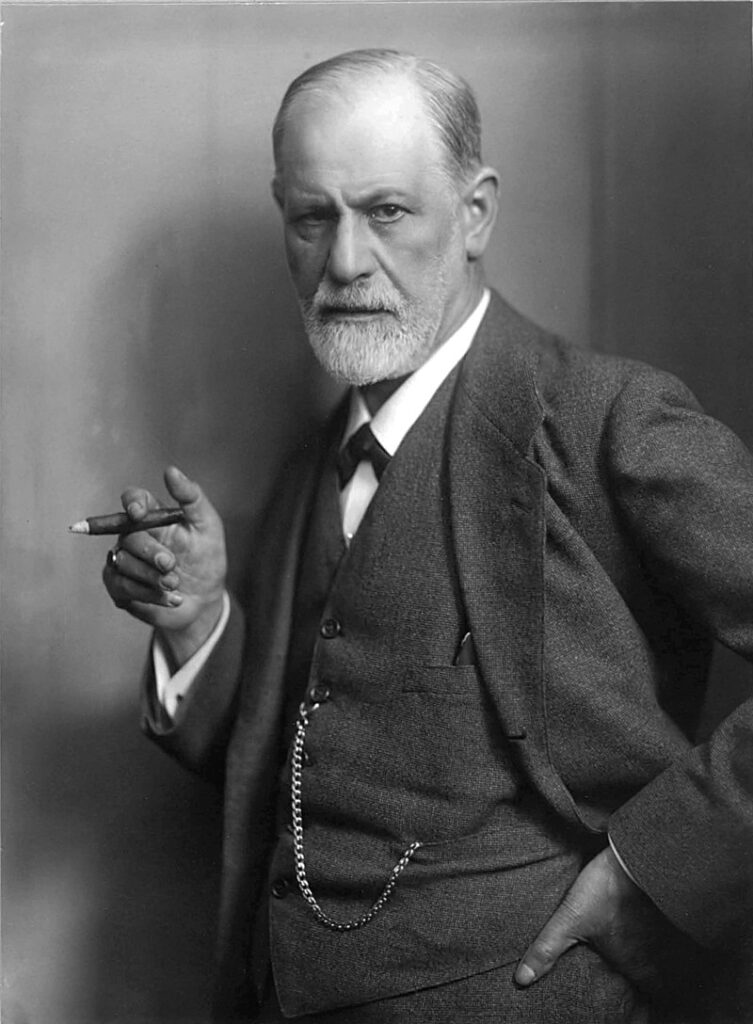

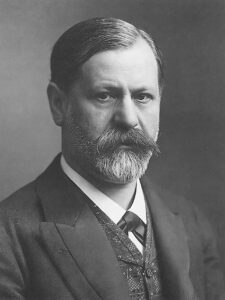

At the dawn of the 20th Century, one young doctor in Vienna developed a theory that would change our understanding of the human mind forever. Using cutting edge techniques the doctor delved further into the psyche than anyone had before. He created names, like the Id and Superego, that are still in use today. Catalogued patterns of thinking, like transference and the Oedipus Complex, that still influence us over a century later. Even now, his name is still instantly recognizable: Sigmund Freud.

Born in the mid-19th Century in what was then the Austrian Empire, Freud’s life was that of a consummate outsider. He was an ethnic Jew in a city of Catholics; an atheist in community of practicing Jews. In a time of intense conservatism, he preached that everyone was bisexual, and shocked society when he suggested erotic desire was rooted in childhood trauma. The father of psychoanalysis, the inspiration for surrealism, and a maverick who courted controversy, Freud ushered in our modern notion of the mind. Yet he died in exile, persecuted and loathed by the city he’d dedicated his life to.

Oedipus Freud

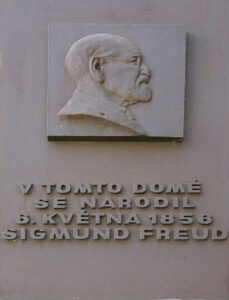

If you were to leave Vienna and walk due north for 150 miles, you would eventually come to a little town called Příbor.

A small, somewhat pretty place, Příbor is utterly unremarkable among Czech towns in almost every respect. With one exception.

It was here, on May 6, 1856, that Sigmund Freud was born.

At that time, Příbor was a heavily Catholic town in the Austrian Empire with the German name of Freiberg, and a Jewish community so tiny you could count its members on one hand.

But small didn’t mean persecuted. Freud managed to be born at a fortuitous time for Jews in the Austrian Empire.

Just a few years before, the new emperor, Franz Josef, had decreed the law would stop persecuting other religions.

No longer would the Empire’s Jewish inhabitants be subject to ghettos and restrictions. They would be free, even to live unrestricted in the imperial capital of Vienna.

Not that the Freuds immediately took advantage of this right.

The first few years of Freud’s life were passed in the pleasant dullness of Příbor, a dullness that nonetheless masked an eccentric upbringing.

Freud’s father Jacob was by now on his second marriage, and his mother Amalie was twenty years Jacob’s junior.

One consequence of this was that, by the time Freud was born, he already had a nephew a year older than him.

John was Freud’s first great friendship. As toddlers, the two were inseparable. But, as Freud would later remark, they were also rivals.

That model of an intimate male friendship that was also overshadowed by great rivalry would be one that repeated throughout Freud’s life.

In 1859, Freud’s older half-brother took John and moved away to Manchester in England.

At first, Freud tried to fill the hole of John’s frenemyship by becoming unhealthily close to his mother, but while Amalie doted on her boy, she was also by now heavily pregnant.

Needless to say, the subsequent glut of four girls and two boys vying for Amalie’s attention would make young Freud crazy jealous.

That same year, 1859, Jacob’s business collapsed and he moved the family to Leipzig.

But things were no better in Saxony and, in 1860, the Freuds joined the mass influx of Jews from across the Austrian Empire moving to Vienna.

The austere capital of a deeply conservative monarchy, Vienna in 1860 was a European power center, but one with a dull reputation; the dowdy sister of elegant Paris and industrious London.

Yet it was also a capital on the cusp of change. As Jewish intellectuals, Hungarian aristocrats, and German artists all converged on the city, the seeds were planted for Vienna’s transformation.

One of the key figures in this transformation would be Sigmund Freud.

The family’s early years in Vienna aren’t much to remark upon. They settled into Leopoldstadt and Jacob presumably got a decent job.

We can infer this because, in 1865, he was able to pay for 9-year old Freud to attend an excellent gymnasium.

And, no, not that sort of gymnasium; “gymnasium” is the Central European term for a specialist school.

During his years at this Lycra-less gymnasium, Freud excelled at academic subjects, developed a voracious appetite for books, and had yet another of his trademark intimate frenemyships, this time with a lad named Eduard.

But it wasn’t until his last year there that Freud made a casual decision that would change his life.

A public reading of one of Goethe’s nature essays was being staged, and the young Freud went along on a whim.

It was while listening to this essay that Freud had a flash of inspiration.

He now knew what he wanted to do with his life.

He was going to study medicine.

Making the Man

The next decade passed in a blur.

In 1873, Freud enrolled at the University of Vienna as a medical student, where he gained a solid reputation as a brain anatomist.

It was while at the University that he was introduced to the older Dr Josef Breuer, a guy who is gonna become really important to our story really soon.

Two years later, in 1875, Freud traveled to England for the first time, meeting up with his old frenemy John. He returned to Vienna obsessed with Britain, despite, as he put it, all the “fog and rain, drunkenness and conservatism.”

By 1881, Freud was a qualified medical practitioner. Barely was the ink dry on his degree than he’d met and fallen in love with his future wife, Martha Bernays.

See what we mean? Busy decade.

Bernays and Freud were soon engaged, but there was a problem.

Martha Bernays came from a highly respected family. Her grandfather had been chief Rabbi of Hamburg. Her parents were used to the finer things.

So when this semi-impoverished wannabee doctor came and asked for their daughter’s hand in marriage, they were all like:

“Uh, no. Come back when you’ve got a decent job and aren’t dressed like a hobo.”

And so Freud found himself, in 1882, suddenly in desperate need of a steady income.

For a Viennese medical student at that time, the best way to get ahead was to do something groundbreaking, get noticed, and use your fame to set up a practice.

While Freud already had a reputation as a brain expert, he had nothing on his CV guaranteed to make his name.

So Freud decided to roll everything on a gamble that couldn’t fail.

He was going to introduce Vienna to cocaine.

We promise we haven’t got confused and accidentally started reading from our old Pablo Escobar script. Freud really was certain that a breakthrough with cocaine was where his future fame – and the money to marry Martha – lay.

In April, 1884, he brought a huge quantity and began experimenting with it as a cure for depression, for indigestion, for alcoholism… anything that might work.

Unfortunately, he missed the one major breakthrough cocaine could have afforded him. It was Freud’s friend, Karl Koller, who discovered it could be used to numb people’s eyes prior to surgery.

By the time a year had passed, Freud’s great foray into cocaine had gotten him nothing but missed opportunities and an expensive addiction. So he decided to change tack.

That July, Freud left Vienna and traveled to Paris to study under the great neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot.

For most of the 19th Century, nervous disorders had been approached from a biological perspective, like fixing a leaky ship. If you could discover where the fault was and patch it, you’d have a whole person again.

But Jean-Martin Charcot had changed that.

Where others would talk about surgery, Charcot was interested in hypnosis. Where doctors in Vienna might whisper about brain structure, Charcot was dabbling with healing patients using only the power of words.

For Freud, witnessing Charcot’s methods was more mind-blowing than a noseful of Uncle Escobar’s marching powder.

Freud returned to Vienna in 1886, certain Charcot’s methods would give him an edge in his competitive field.

At first it looked like another fail. Freud’s contemporaries basically accused him of falling for a load of French merde.

But Freud was determined. He set up his own practice, consulting on nervous diseases using hypnosis. And he soon had a regular enough income to be able to afford marriage.

On September 13, 1886, Sigmund Freud and Martha Bernays were wed. Over the next eight years, their union would produce six children.

For Freud, marrying Martha must’ve felt like the affirmation he’d been waiting for.

Here he was, after all those false starts, owner of a successful practice, and married to the woman of his dreams.

But Freud wasn’t content to just stop now.

He’d gotten a taste for grandiose ideas, for eccentric innovations.

His next one would change medicine forever.

A Brand New Science

Come the mid-1890s, Freud was restless.

He’d been practicing his brand of psychotherapy for nearly ten years now, and was no longer getting the results he desired.

It was while in this despondent mood that he got to talking with his old teacher, Dr Josef Breuer. During the conversation, Breuer just happened to mention one of his own old cases.

Way back in 1882, Breuer had treated a woman he called Anna O.

Anna had been suffering from what used to be called hysteria, a catch all term 19th Century doctors used to mean anything from seizures, to anxiety, to being too unladylike.

But Anna had also been strong willed. She shrugged off Breuer’s attempts to use hypnosis, and suggested they work via talking.

Over the next few weeks, patient and doctor developed something they called the “talking cure”.

Instead of Breuer using hypnosis to implant suggestions, he’d just allowed Anna to unburden herself, a kind of cathartic release.

The idea that you could use talking to get at hidden trauma was the craziest thing Freud had heard since his days with Charcot.

Naturally, he loved it.

In 1895 he helped Breuer write a case study they published together as Studien über Hysterie.

However, Breuer was uncomfortable with Freud’s obsession with his case.

Despite what he claimed, Breuer hadn’t actually cured Anna. She was still in decline, and today it’s thought unlikely Breuer’s treatment was helpful.

Still, Freud persisted. He began introducing the talking method to his own practice. Invented the classic psychoanalyst set-up we know from movies: y’know, with the patient lying on a comfortable couch, while the doctor sits out of sight, taking notes.

Pretty soon, Freud was using free association to get his bourgeois patients to talk about their darkest desires.

And he kept finding out that all of them were obsessed with sex.

So, this is where we get to the first of many controversial parts of Freud’s work.

All of Freud’s patients were female, and it’s a frequent accusation that Freud was simply pathologizing ordinary female sexuality.

Whether or not that’s true, Freud soon came to believe that our hidden desires were at the root of many of our problems.

Before long, he’d coined a term for the process of treating these problems: psychoanalysis.

But if you’re expecting to hear this is the beginning of Freud’s rise to becoming a household name, you may have to think again.

For Freud, the late 1890s were spent in the intellectual wilderness.

Sure, things were OK financially. And his home life was going fine. Martha had just given birth to their youngest daughter – the future child therapist Anna Freud.

But Freud’s reputation was floundering. His initial attempts to create a handbook for psychoanalysis collapsed. Among the Catholic establishment, there were rumblings that Freud was wasting his time with some “Jewish science”.

Once again, Freud was in need of a breakthrough to put his name in the spotlight.

In 1897, he found it.

Up until that point, Freud had listened as many of his patients described what appeared to be sexual abuse in their childhoods.

Before 1897, Freud had tended to believe them. That year, he changed tack.

Freud’s eureka moment was deciding the abuse his patients reported wasn’t real.

Instead, it was all fantasies brought on by repressing their sexuality in childhood.

And here we get to yet another controversial segment.

Nowadays, it’s acknowledged that children experience immature sexual feelings, usually in the form of embarrassing crushes or really, really wanting to hold Chloe’s hand during recess.

But we also acknowledge that some adults really do abuse children. Even adults from respectable, middle class families.

It’s far from certain, but some argue Freud unwittingly helped cover up a culture of abuse in Vienna.

Still, the breakthrough gave Freud the notoriety he’d always craved.

Now he just had to convince the deeply conservative society he lived in to take his wild thoughts on sexuality seriously.

How hard could that be?

Breakthrough

If the 1890s were Freud’s wilderness years, the first decade of the 20th Century was Freud marching in from the desert, kicking down the gates of Vienna, and forcing the world to listen to his ideas.

In 1900, Die Traumdeutung – know in English as The Interpretation of Dreams – hit the bookshelves with all the force of a bomb going off.

The basic outline of Freud’s thesis was linking dreams with repressed desire, often stemming from childhood, while also talking about fantasy and daydreams reflecting unconscious wants.

If that sounds a little abstract, know that this book is where the idea of the Oedipus Complex comes from, something that we still talk about over a century later.

But the most consequential part was Freud’s insistence that his discoveries didn’t just apply to his patients.

They were universal. This great ocean of dark desire was roiling away in all of us.

It was this insight that would ensure Freud’s name went down in history.

Starting in 1902, Freud followed up Die Traumdeutung with regular lectures at Vienna University. Although the number of attendees was small, there was a core, loyal group.

Before long, that group was meeting with Freud every Wednesday to discuss psychoanalysis.

By 1908 they would grow into the hugely influential Vienna Psychoanalytical Society.

As these meetings began to spread Freud’s ideas, the man himself was hard at work, churning out book after book.

First came Zur Psychopathologie des Alltagslebens (The Pathology of Everyday Life), which introduced the world to Freudian slips – disappointingly not a lacy undergarment you wear to seduce your mother, but the act of accidentally saying something revealing.

This was followed in 1905 by Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria, which first diagnosed the phenomenon of transference.

It was around this time that Freud’s growing fame brought him into contact with Carl Jung.

To say Jung was important to Freud’s life is like saying the Civil War probably affected Abraham Lincoln’s career.

Their collaboration was intense and tragic. Intense because their meetings would turn into nonstop 13 hour debates. And tragic because… well, you’ll see.

In Jung, Freud saw someone who could make psychoanalysis mainstream. Both because Jung was twenty years younger, but also because he was a gentile.

He may have been an atheist all his life, but Freud was only too aware of how Europe saw even nonobservant Jews. That his discoveries could be pigeonholed as mere Jewish quackery.

For several years, the collaboration spurred both Freud and Jung to greater heights.

Jung was there when Freud held the first international psychoanalytic congress in Salzburg.

He was there when Freud gave his only lecture series in America, at Clark University, Massachusetts.

And he was there, defending Freud in the public eye whenever his ideas were ridiculed.

Alas, it was not to last.

In 1913, resentments that had been building between the two men finally came exploding out.

There are many theories about what caused their rift, but given today’s subject, it seems only fitting to highlight one particularly Freudian interpretation.

We know that Freud occasionally fretted he had a gay side – indeed, he claimed all humans were innately bisexual – and that he may have harbored repressed feelings for Jung.

We also know that Jung had unresolved anger issues relating to his father, feelings he often directed towards father figures like Freud.

Whatever the truth, the break between the two men was permanent.

In 1913, Freud wrote the younger man a letter, telling him he never wanted to see him again.

Jung seems to have agreed. He never tried to contact Freud again.

It was the end of a period of intense creativity for Freud, and the end of his dreams of grooming a successor.

But that time period was also the end of something else, too.

Freud didn’t know it, but he was living through the last days of Europe.

The End of a World

The First World War was like a wrecking ball crashing into the house of cards marked ‘history’.

In the short years between 1914 and 1918, the war swept away three whole empires, including Austria-Hungary.

Come late 1918, Vienna had gone from being a seat of European power to the backwater capital of a small, impoverished nation known simply as Austria.

For Freud, the war had been marked by the constant threat of tragedy, both personal and professional.

On the personal side, all three of his sons had been drafted to serve in the Austro-Hungarian Army, making the death of at least one of them seem almost inevitable.

On the professional side, the outbreak of war killed the international psychoanalysis movement stone dead.

For four long years, Freud was confined to Vienna, able to do nothing but write, think, and dream of a better future.

It was during this period that the lifelong cigar smoker first discovered a strange growth on his jaw.

Yet Freud was lucky. All three of his sons came back alive from the front.

And when the war ended in 1918 and the economy of Austria was battered by runaway inflation, Freud was able to take British clients to provide his family with hard currency.

For the lifelong anglophile Freud, this was a dream come true.

His patients were from the famous Bloomsbury set, a collection of freethinking writers and artists.

When they came to him for treatment, Freud made it a condition that they translate his works into English.

It was this agreement that would eventually make Freud a household name.

Yet it was also in this postwar period that tragedy finally struck.

In 1919, a virulent new strain of influenza swept the world.

Known as Spanish Flu, it remains one of the deadliest pandemics in history. In one short year, it killed up to 50 million people.

Among that 50 million was Freud’s daughter, Sophie.

The death of Sophie came as a devastating blow to Freud. Barely had he recovered than he himself was diagnosed with cancer of the jaw.

It was the start of a long decline from which Freud would never recover.

But life goes on. As the Great War gave way to the Roaring Twenties, Freud continued to write, publishing Das Ich und das Es (The Ego and the Id), the work that gave us terms like superego that are still in use today.

He also began to focus on his daughter Anna’s development, taking her to psychiatric conferences, and increasingly sending her in his place when the cancer left him too weak.

It was around this time, when Freud was at his lowest ebb, that psychoanalysis really began to take off.

In Paris, the surrealists founded an entire art movement inspired by Freud’s discoveries.

In Vienna, Freud found himself suddenly treating the fabulously wealthy, like Marie Bonaparte, a descendant of Napoleon.

By the end of the twenties, you could even convince yourself Freud’s life was getting back on track.

The cancer still hadn’t killed him. He was publishing books like Civilization and its Discontents, and psychoanalysis was taking off in America

But sadly, we already know this was just an illusion.

From our vantage point of the 21st Century, we can already see the clouds gathering on the horizon. The storm that will be unleashed by one nationalist with a fanatical hatred for Jews.

For the Jewish Freud, still living in Vienna, that storm would be destined to consume him.

Burning Books, Burning People

On May 10, 1933, a large group of students gathered outside the State Opera in Berlin.

But these students weren’t there to down kegs or party.

They were there to burn books.

Barely two months earlier, the German parliament had passed the Enabling Act, handing total power to Adolf Hitler.

Now the Nazi student groups were showing their enthusiasm for the new regime by consigning 25,000 “un-German” books to the flames.

Among the books that burned that day were the works of Sigmund Freud.

In Vienna, Freud could only watch as neighboring Germany fell to Nazism.

His sole consolation may have been that Austria hadn’t yet succumbed.

Although fascists seized control of the country in 1934, they stopped short of the outright anti-Semitism of the Nazis.

Still, the growing violence in Germany must’ve put everyone on edge. What if Hitler decided to take over Austria?

In 1938, he finally did.

On March 12, German tanks rolled across the border, annexing Austria into the Third Reich.

On the streets of Vienna, people lined up to cheer the Nazis. Buildings were draped in Swastikas, street parties held.

All alone in his apartment, Freud simple noted two words in his diary: ‘Finis Austriae’.

By this stage, Freud was nearly dead from the cancer spread throughout his system; a walking cadaver that couldn’t even make it to the family’s summerhouse outside Vienna.

When people suggested he leave the country he told them it would never happen.

Nor would it have, had it not been for what happened to Anna.

On March 22, Anna Freud was arrested by the Gestapo. They ruthlessly interrogated her for hours before throwing her back out onto the street.

The incident shook the elderly Freud to his core. The next day, he decided to leave Austria.

This was easier said than done.

Under the new Nazi regime, the whereabouts of Jews was closely tracked. Leaving the country required a special exit visa, and you can guess how often the Gestapo handed those out.

Thankfully, Freud had three very important people on his side.

The first was his patient, Marie Bonaparte. The second was William Bullitt, the US ambassador in Vienna.

But the third was less expected.

Komissar Anton Sauerwald was a dyed in the wool Nazi, tasked with overseeing Jews in Vienna.

But Sauerwald was also a former student of one of Freud’s closest friends. He’d spent all his years of study learning to respect the famous doctor.

So when he discovered Freud was looking for an out, he decided to help him.

That Spring, Sauerwald secured exit visas for Freud and 16 of his family members. Elsewhere, Princess Marie was using her vast fortune to grease as many palms as possible, while William Bullitt was applying diplomatic pressure.

After three months, the Freuds were finally given the all clear to leave Austria for England.

The ride to London must’ve been both hopeful and heartbreaking.

Here was Freud, finally fulfilling his teenage dream to live in England, but under the gloomiest circumstances.

It probably didn’t help that all four of Freud’s elderly sisters had been unable to get exit visas. Although Freud wouldn’t live long enough to hear the news, all four would perish in concentration camps.

On June 6, 1938, Freud and his family finally arrived in London by train.

Word had leaked out, and a huge crowd had gathered to welcome the world’s most famous psychoanalyst.

As he saw the rows upon rows of people cheering, Freud felt like he’d finally come home.

Freud would live barely a year after reaching England, passing away on September 23, 1939, just twenty days after Britain declared war on Germany.

He kept receiving patients almost until the very end. When the author H.G Wells came to visit, Freud confided in him that it had always been a fantasy of his to be an Englishman.

In its own strange way, that fantasy had come true.

Today, it’s fashionable to knock Freud’s theories, to poke fun at his experiments with cocaine, his obsession with sex.

Certainly, there are few psychiatrists today who would say Freud’s methods were completely sound.

Yet to just focus on Freud’s medical work is to miss the point.

No matter what you think of him, Freud completely transformed the way we understood the human mind.

Just think how often you hear about people having “complexes”, or suffering from transference, or having problems with mother or father figures.

Think how deeply ideas of psychoanalysis and childhood trauma have penetrated into our fiction, into our art. Think just of how significant surrealism became.

Sigmund Freud may have died an exile, unloved by his home country. But he also died the father of psychoanalysis, and the greatest explorer of the human mind.

For that reason, if no other, he deserves to be remembered.

Sources

Super in-depth bio, slightly confusing version: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sigmund-Freud

In-depth bio, but easier to read: https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-55514

Interesting podcast. Includes references to how much Freud disliked biography(!): http://podcasts.ox.ac.uk/freuds-impossible-life

Simple biographies: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/freud_sigmund.shtml

https://www.biography.com/scholar/sigmund-freud

Freud and Jung: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/genius-and-madness/200905/why-freud-and-jung-broke

Freud and Jung, alternative view: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evil-deeds/200905/freud-jung-and-their-complexes

Freud’s letter to Jung: http://www.openculture.com/2014/06/the-famous-letter-where-freud-breaks-his-relationship-with-jung-1913.html

Anna Freud’s Gestapo arrest: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/freud-nazi-germany_b_1392377

Freud on everyone being bisexual: https://global.oup.com/us/companion.websites/9780199315468/student/ch4/wed/freud/

Freud on cocaine: https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/payngv/a-brief-history-of-freuds-love-affair-with-cocaine