Author: Debra Kelly

New York City. The Big Apple. It isn’t the capital of the United States, but it’s still the country’s beating heart. It’s wild, weird, and wonderful, and in order to truly understand how it turned into the metropolis it is today, you’ll have to take a look at one of the most influential figures in the city’s history. It’s a tale of corruption, fraud, bribery, ostentatious wealth, a little bit of creative legal interpretation, and a lot of sheer audacity and willpower.

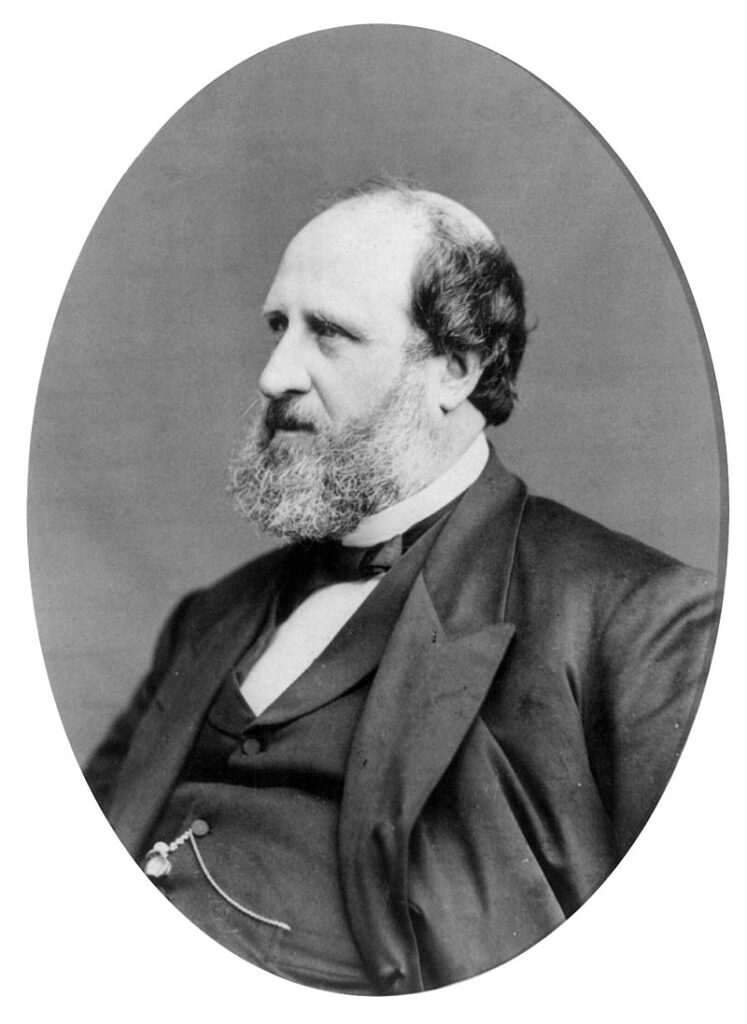

One of the most important figures of 19th century New York was William Magear Tweed, also known as “Boss” Tweed and the Tiger of Tammany, for reasons that will soon become clear. On one hand, Tweed was responsible for building some of the infrastructure that made it possible for the city to grow. He improved the water and sewer systems, built city streets, and oversaw the construction of major landmarks, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Central Park, the Brooklyn Bridge, and the American Museum of Natural History.

On the other hand, he was one of the most corrupt politicians ever to rise to power in the US. By the time he died in 1878, it was estimated that he and his network of cronies had stolen millions from the state — a sum that’s estimated to be as much as $3.5 billion in today’s money. How? That’s at the heart of our story today.

Street-fighting firemen

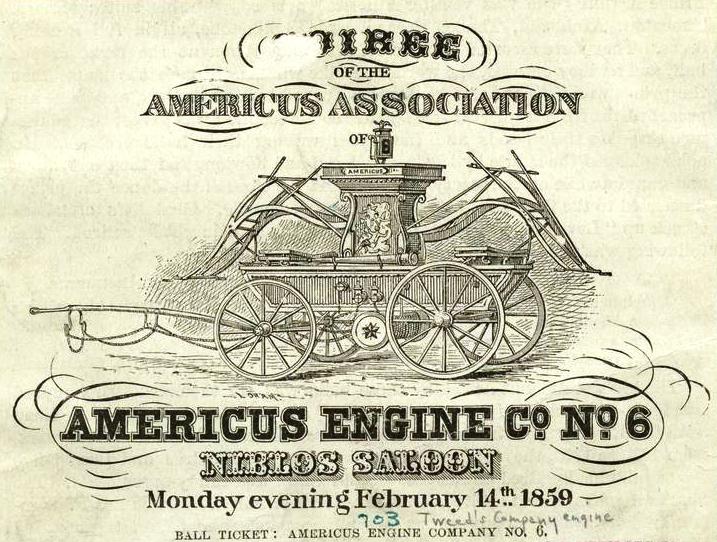

Tweed was born on April 3, 1823, and according to most accounts, he had an average childhood. He had the basic sort of education typically available to children growing up in Manhattan at the time; he once completed a brief stint as a chairmaker’s apprentice. Tweed’s life seemed to take a dramatic shift when, as a teenager, he attached himself to his local volunteer fire company. Here’s where a bit of a secondary history lesson is needed to truly do the story justice.

The volunteer fire fighting companies of the mid-19th century were nothing like the ones of today. As a fairly new idea, volunteer companies and they were half-gang, half fraternity, with only a small amount of effort reserved for actual firefighting. Companies inspired strong allegiances among their members and were closely tied to the local politics of their area. It wasn’t unusual to have more than one company racing to put out a fire, only to get distracted by the sight of a rival company and have the entire thing dissolve into a massive street brawl.

And even as a teen, Tweed had quite the reputation as one of his company’s best brawlers.

Tweed had attached himself to Engine Company 33, which was also known as Black Joke. For an idea of just what sort of folks this particular engine company attracted, let’s jump ahead a few decades for just a moment. In 1863, New York was torn apart by a series of draft riots that led to more than 100 deaths and somewhere around $1.5 million in damages. Leading the way were the men of the Black Joke, angry that firefighters weren’t exempt from the draft that was sending able-bodied men from across the city to fight in the Civil War. They started by burning the city’s draft office, and it kicked off a full-scale riot that descended into race riots so bad that the fire company retreated from the front lines and went to defend their own neighborhood from the burning, pillaging, and beatings.

That is the company Tweed joined as a teen, where he first made a name for himself.

After establishing himself as a charismatic yet street-smart figure in the neighborhood, he kicked off his political campaign and secured a position as alderman of the Seventh Ward. (An alderman is a judicial official that oversaw some minor civil and criminal cases, and worked closely with the mayor.)

That was in 1852. Tweed rose through the political ranks fast. By 1853, he had a seat in the House of Representatives. Life in Washington, DC didn’t suit him, however, and he headed back to the city after just a single term. He’d kept his finger firmly on the pulse of the city’s political scene, and in 1856, he landed a position on the city’s new board of supervisors. From there, he didn’t look back.

Taking over at Tammany Hall

Now, a little background about one of the organizations that shaped New York City through the 1800s. Tammany Hall was founded in the 1780s, and it was originally meant to be a fraternal society where like-minded individuals could get together, socialize, and talk about politics. Their actions became increasingly political as the decades went on, and by the 1840s, they had firmly established themselves as an arm of the Democratic party. Even more importantly, they had developed a deep connection with the city’s ever-growing population of immigrants — particularly the Irish. Tammany Hall helped countless new arrivals get jobs, set up lives, and even get achieve US citizenship. In turn, Tammany Hall got votes for the candidates they put forward in elections across the city and state. It seemed to work out for everyone.

Tammany Hall always had the stink of corruption about it. As early as the 1850s, it was clear that those who were capable of rising to power within the organization were also the type to color outside the lines. Isaac Fowler was the Grand Sachem — in other words, the boss — before Tweed stepped into the position in 1868, and his term ended when he was charged with embezzlement and fled to Mexico. In spite of the scandal, the political machine that was Tammany Hall kept increasing their influence over the city — this time with Boss Tweed at the helm.

Tweed spend most of the decade establishing himself in the neighborhood, where he was already known as a larger-than-life character — literally. At a time when the average height for a man was around 5-foot-6, Tweed towered over most at an impressive height of about six feet. He topped the scales at almost 300 pounds, too, at a time when the average weight was closer to 150. Add in the 10-and-a-half carat diamond he liked to wear all the time, and you had an imposing figure, indeed.

It was easy for such a memorable man to be the center of attention, and that was a significant part of why Tweed was so successful. He wasn’t just a politician sitting up on high, raking in the cash. He was on the streets, shaking hands, handing out cigars and whiskey, and — perhaps most importantly — listening to his constituents. Tweed was famous for remembering names and faces, investing himself in the stories that people had to tell, and ultimately, doing them favors. True, those favors often had another attached in return, but as Tweed was climbing the political ladder, he had an impressively modest reputation for honesty.

Tweed, immigration, and voter fraud

Many of the positions that Tweed and his associates held were still elected positions, and that brings the story around to another important point: just how did Tweed’s squad manage to get themselves elected so regularly? A big part of their success was the fact that the ever-growing population of Irish immigrants saw them as an organization that truly cared about their welfare. Many had fled The Great Famine, a catastrophic crop failure in Ireland that led to the deaths of somewhere around a million people. When starving families of survivors reached New York, Tammany Hall welcomed them with open arms. They even helped them out with baskets of food and coal for their fires.

But it wasn’t all good will. Tweed was notorious for a brazen scheme where he would recruit a few dozen volunteers from among their loyal followers, ply them with alcohol, and register them in multiple polling places. Then, he would pay law enforcement officers to escort them from one polling place to the next, and to make sure they cast their votes. One person would vote dozens of times, and that all added up to votes for Tammany Hall.

None of this was a secret. Tweed also paid the officers to arrest any voting inspector that started to get suspicious.

The most flagrant instance of Tweed using his clout and influence with immigrants to get Tammany Hall allies more votes came in 1868. That’s the year that Tweed arranged to have around 44,000 immigrants become naturalized citizens in the weeks before a major election. It didn’t go unnoticed, either; when Tammany Hall members were elected to offices at the mayoral level, and all the way up to governor of New York, the House of Representatives put together a committee to determine the extent of Tweed’s interference with the elections. Nothing came of it.

The so-called Tweed ring — only continued to increase their power and influence. The same year he was under investigation for interfering with elections, Tweed was named to the head of Tammany Hall and elected to the New York Senate. Those were just stepping stones, though. While Tweed was serving as House Rep at the federal level, he had made friends across party lines. That allowed him to pass a charter shifting the responsibilities of local governance — particularly those that concerned budget and oversight — out of the hands of federally appointed boards and into the control of locally appointed authorities.

And that was the truly brilliant part. Remember when we mentioned that Washington, DC hadn’t been to Tweed’s liking, and he opted to leave federal politics to head back to New York City? When he did, that very same city charter was waiting for him, and it passed complete control of the treasury into his direct authority. He and his cronies now had absolute control over what the treasury paid out, and they took advantage of it in every way they could.

The Tweed Courthouse

No building or enterprise illustrates the extent of the Tweed Ring’s corruption better than the Old New York County Courthouse. The building is a stunning display of 19th century architecture and craftsmanship, and it’s also known as one of the most prominent legacies of Tweed reign at Tammany Hall. It also ended up being the most expensive building ever built in the United States at the time, costing even more than the US Capitol Building, for the simple reason that Tweed and his cronies were in charge of both issuing the bills and paying them from the city’s coffers.

The Tweed Ring was unthinkably audacious when it came to manipulating these construction bills. The original budget for the entire building was $250,000, a hefty sum for the time. To give an idea of just how much the courthouse ended up costing, that original budget was only enough to pay the bill for the purchase of the courthouse’s brooms.

Other items were just as costly. Plumbing set the city back more than $1 million, the thermometers ended up at a rather pricey $7,500, and a set of three tables and four chairs came to a grand total of $179,729. And there were a lot more of these “chairs.” For the amount of chair money that Tweed actually billed the city for, they could have bought around 315,000 of them — and that’s somewhere around 17 miles of chairs.

Carpets for the courthouse cost around $5 million, largely because there was enough carpet ordered to cover City Hall Park three times. What did they do with all that carpet? Nothing, because it was ordered from companies that didn’t exist.

Some companies did exist. Before construction started, Tweed had conveniently bought a quarry. It was that quarry that was used to source all the marble for the courthouse, and that bill alone was higher than the entire cost of building another courthouse in Brooklyn.

Not all of the money was going right into Tweed’s pockets, as he also made sure his fellow officers at Tammany Hall were well cared for. The grand marshal at the time was Andrew J. Garvey, and he earned the nickname “Prince of Plasterers” after he ended up pocketing around $3 million for the work he did on the courthouse, and for subsequent repairs to his original labor.

So, how much did it end up costing? When the state legislature approved the build for $250,000, that was the equivalent of around $6 million in today’s money. When it was finally finished, the bill hit $12 million. Adjusted for inflation, that’s about the equivalent of $200 million today. It’s no wonder that people started catching on.

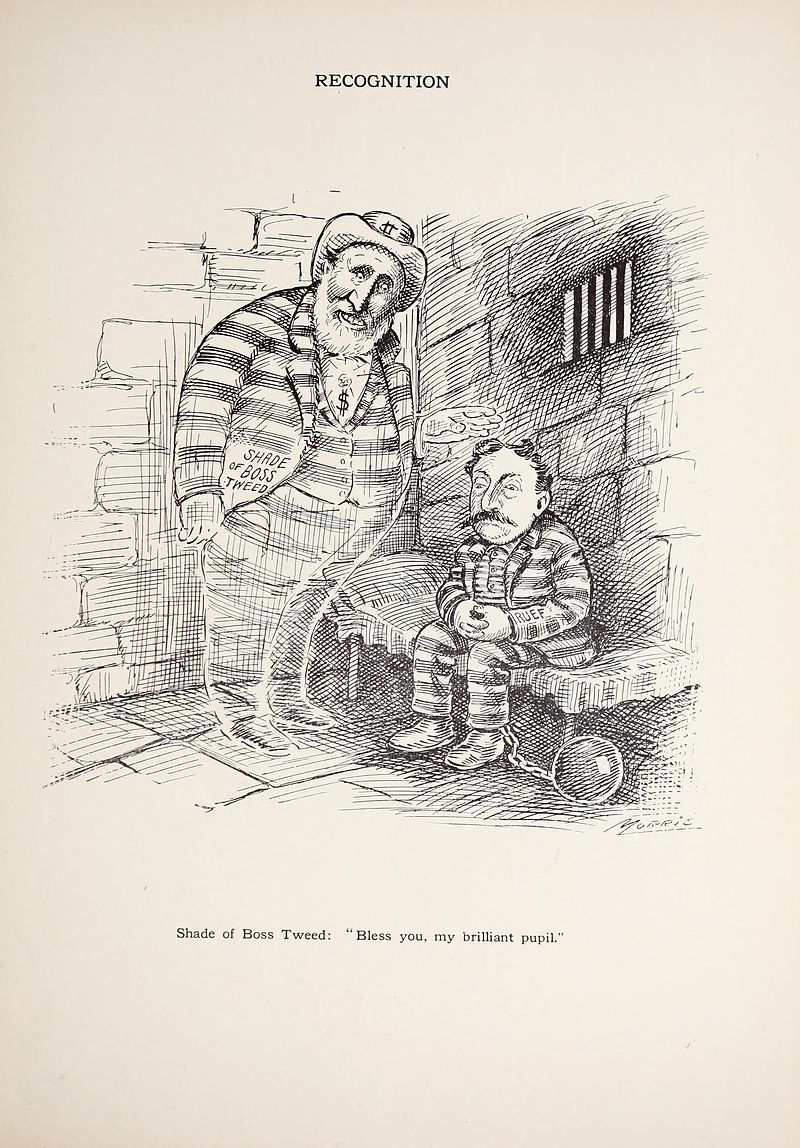

The power of editorial cartoons

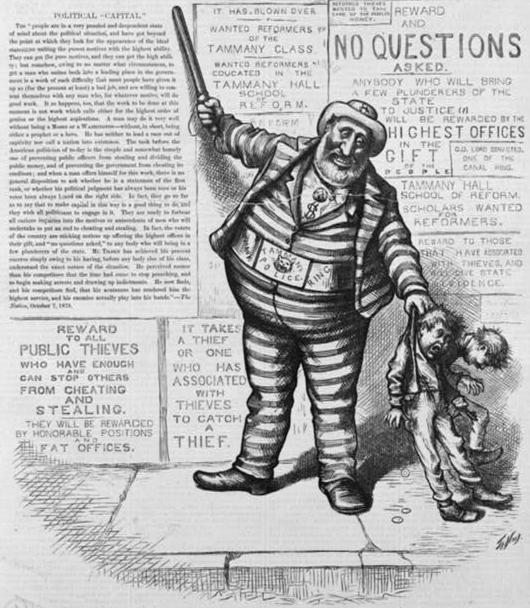

While there were plenty of people willing to look the other way when it came to Boss Tweed’s criminal ways, not everyone was so willing to allow the Tweed Ring to keep running riot across the city. One of those determined to bring down the corruption of Tammany Hall was Thomas Nast.

Nast was a German immigrant who settled in New York City and discovered very early in life that he had a natural artistic talent. The timing was excellent; with the start of the Civil War, Americans were growing increasingly interested in what was going on in other parts of the country and, specifically, in the war. Newspapers were still the way many people got their information, and Nast’s drawings of some of the most famous battles of the war catapulted him to fame. He was one of Abraham Lincoln’s favorite propagandists, and he took on the big issues of slavery, war, and eventually, political corruption. That was a bigger deal than you might realize, because his illustrations reached an entire group of people who otherwise wouldn’t have cared much for what was in the paper. Those people were illiterate.

Nast was working at Harper’s Weekly when Tweed was running Tammany Hall. His campaign to shine a spotlight directly on the rampant political corruption that dominated the institution started by his calling them on voter fraud, and it only escalated from there.

Early on, Nast — along with reporters at the New York Times — struggled to get something to stick to the Tweed Ring. Despite the fact that everyone knew what was going on, uncovering concrete evidence proved difficult.

…Until 1871, that is.. While Tweed had gone above and beyond to keep his constituents on his good side, Nast was not so easily swayed. It’s also important to note that Nast’s campaign wasn’t out of any righteous indignation or a determination to clean up the city, no matter what the cost. Nast was a rabid devotee of the Republican Party, and as such, he staunchly opposed the idea that the Irish working class immigrants were anything but trouble. Since Tweed was so closely allied with that portion of New York City’s population, he clearly had to go.

And on July 18, 1871, Nast and his colleagues at the Times were given a gift. One of Tweed’s associates was a man named Jimmy O’Brien, and O’Brien believed he wasn’t being treated fairly, in the grand scheme of things, so he did something that had to have taken an insane amount of courage — he took duplicates of the city’s ledgers, strolled into the Times, and handed them to an editor named Louis Jennings.

Then, he walked away.

The Times began running all the sordid details of Tweed’s operation, and that’s when Nast really swung into high gear. Until this moment of reckoning, when they were handed actual proof and concrete numbers, his cartoons were mere personal attacks. He couldn’t prove anything aside from the fact that he was wealthy, but making fun of that had no real effect.

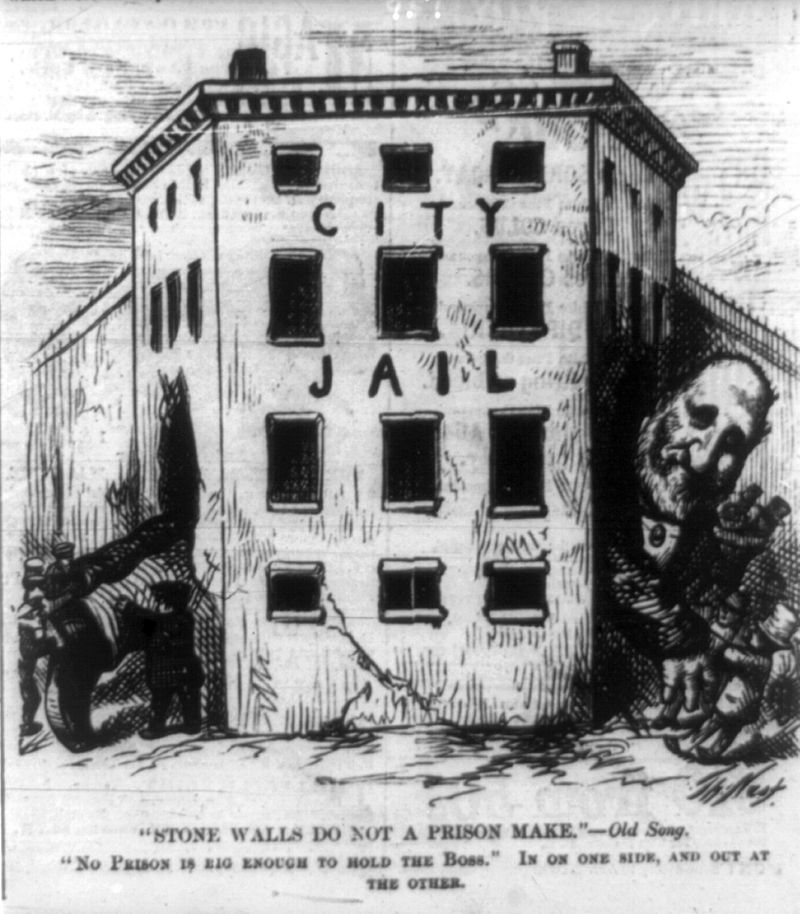

But when Nast started drawing cartoons showing Tweed as a fallen emperor, as passing the blame onto others, and as seeing himself as too powerful to be contained by a prison, it was illustrating a more abstract situation in a way that everyone could understand. And it was Boss Tweed himself who best summed up the problem he now had: “I don’t care a straw for your newspaper articles. My constituents don’t know how to read, but they can’t help seeing them damned pictures.”

It was all downhill from there.

The fall

Things started happening fast after O’Brien handed over proof of just what Tweed and his cronies had done to the city. Members of the Tweed Ring started to flee the country ahead of the fallout they knew was now inevitable, and Tweed himself was arrested in October. Surprisingly, he was released on bail and allowed to run in a local election, and even more surprisingly, he still won. But the end was nigh, and the following few years would be marred by a series of trials appropriately held in the still-unfinished Tweed Courthouse.

It wasn’t until 1873 that Tweed was found guilty of 204 of the 220 charges brought against him. He was sentenced to serve 12-year jail term that was quickly reduced; he was also ordered to pay a $12,750 fine.

Even at the same time Tweed lost his freedom, Tammany Hall lost their boss. But it wasn’t the end for them. They passed their leadership into the hands of a man named John Kelly. He made major strides in overhauling Tammany Hall and its image, turning it into something more in line with what anti-corruption campaigners and reformers had in mind.

It didn’t last long, though. Voter fraud came back with the very next leader, who took over in 1888. By the beginning of the 20th century, there was another group that had a vested interest in Tammany Hall: the mob. When it came time for the 1932 presidential elections, the Tammany Hall delegates were escorted to the Democratic National Convention by the likes of Meyer Lansky, Lucky Luciano, and Frank Costello. Afterwards, Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivered some major blows to the all-encompassing power of Tammany Hall — in part, by restricting immigration and limiting their core supporters. Things were never quite the same, and after a brief scramble for power in the 1950s, Tammany Hall disappeared in the mid-1960s, its doors closed and its properties sent to auction.

But now, back to Tweed as his story isn’t quite over yet. It turned out that even his jail time wasn’t much of a punishment. Tweed served his time in a private room in Blackwell’s Island, with a window looking out over his domain. When his year was up, he was brought up again on civil charges. Prosecutors were hoping to recover some of the money that he had funneled out of the city’s coffers, and when he was unable to make bail this time, he was confined to the Ludlow Street Jail.

There is, of course, a “but”. Tweed’s cell was a two-bedroom set of rooms with a small library and his own personal aide. He talked the warden into letting him have regular visitors; he was even allowed to head out into Central Park for the occasional carriage ride.

On December 4, 1875, he headed to his home with an escort of two guards. After telling them he was going to check on his sick wife, he strolled out the front door, crossed the Hudson River in a carriage, and escaped to New Jersey, where he went on the run under the alias “John Secor.”

In the meantime, the courts had continued without him and ruled that, yes, he did owe the city $6 million dollars. With nothing really left to lose, Tweed continued life on the lam, hopping on a schooner and sailing down the Atlantic coast. He met up with a man who was going by the name of William Hunt. It’s not entirely clear who Hunt was, but we do know that the duo hopped a fishing boat to Cuba. They were immediately stopped for not having the proper paperwork, but before the governments could coordinate to arrest him, he jumped on yet another boat bound for Spain.

Unfortunately for Tweed, the six-week crossing gave authorities more than enough time to send word to Spain that they had a fugitive headed for their shores. Spanish officials were waiting on the dock for him when he got there.

There’s one last little footnote to the story that adds to the sheer outrageousness of the tale — the authorities weren’t sure who they were looking for, but they were able to identify Tweed based on one of Nast’s cartoons. It was, appropriately, one that depicted him in the striped outfit of a convict.

Hunt was released, but Tweed was shipped back to the US. Only 11 months after escaping, he was back in his old Ludlow Street cell. He was 100 pounds lighter with hair that had gone completely white. He was a broken man.

Tweed finally agreed to confess to everything he’d done in exchange for his freedom, and in 1877 he went before a special committee and not only admitted just how much money he’d stolen, but he also named names. The list was long, and included anyone who had ever taken bribes to look the other way for those who had helped with his election fraud, or those who had taken kickbacks on his construction projects. In the end, the governor and attorney general thanked Tweed for his cooperation, withdrew their promise to set him free, and sent him back to Ludlow.

Two weeks later, on April 27, 1878, he died. He was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery, and he left New York City a place entirely different from the one where he had been born.