By Arnaldo Teodorani

Being the 2nd born child in a Royal Family can be a blessing in disguise. Nobody expects you to rule, so in a way you are off the hook. But sometimes history gets in the way and unexpected events can bring you in the limelight and on the throne. That throne and that crown may represent one of the youngest, smallest and most peaceful nations in Europe, but that does not mean that trouble won’t get in your way.

This is what happened to today’s protagonist, one of the longest serving and most respected Royals of the 20th Century: King Haakon VII of Norway, the voice of dignity against traitors and invaders.

Prince Carl

At the time of King Haakon’s birth, Norway was part of a Union with Sweden. It had an independent cabinet of ministers and its own parliament, but the formal head of State was the King of Norway and Sweden: Carl IV, from the House of Bernadotte, based in Stockholm. Therefore, Norway did not have a ruling dynasty of its own.

The man who would become the King of Norway was actually a Danish Prince: born near Copenhagen on 3 August 1872, in Charlottenlund Palace, he was the second son of the Crown Prince Frederik and Crown Princess Louise of Denmark.

At birth he was christened as Christian Frederik Carl Georg Valdemar Axel, known simply as ‘Carl’ by those with shortness of breath. His elder brother would also become king in the future, King Christian X of Denmark. While growing up, Carl would knock time and again on Christian’s door asking

‘Do you wanna build a snowman?

Or ride our bikes around the halls?’

No, he didn’t. These guys were serious and received extensive private tuition at the Palace. At the age of just 14, Prince Carl began his training as a naval officer. He worked hard along the other cadets, and was not accorded any special privilege. Carl graduated seven years later in 1893 with the rank of sub-lieutenant of the Royal Danish Navy, and was later promoted to first lieutenant.

With that, Carl ticked one of the boxes expected from a Prince: a military career. The second box was finding a suitable match, in other words: meeting and marrying a girl preferably from another European ruling house. At that time, you could not throw a stone into a Royal Palace without hitting someone’s cousin, due to the tight network of familiar relationships amongst rulers.

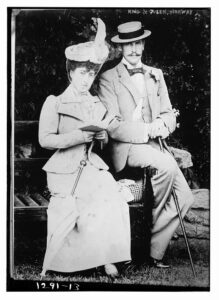

Carl did not stray from the norm and in 1896 he married his cousin from the United Kingdom: she was Princess Maud, the daughter of King Edward VII and his Danish wife, Queen Alexandra. Alexandra was the sister of Frederik, Carl’s father.

If this is getting confusing, here you can feast your eyes with the family tree of the Royal houses of Norway, Denmark, Sweden and the United Kingdom, so you can have fun tracing the blood ties amongst them:

I will post a link to the family tree in the description below, it’s got thumbnails and all for every member.

But let’s not forget about Maud. She was born in London on the 26th of November 1869. Since her early years, Princess Maud attended regularly her mother’s family gatherings in Denmark. It was in one of such occasions that she came to know her cousin Carl.

Their wedding was celebrated in Buckingham Palace on the 22nd of July 1896, and the princely couple settled in Copenhagen. But Carl and Maud always kept strong ties with the UK, and in fact their son and only child, Prince Alexander, was born at Appleton House in Norfolk, England, on the 2nd of July 1903. Little did the young family know that their lives were going to change drastically in just a couple of years.

Haakon

On 7 June 1905 the Norwegian parliament, known as the ‘Storting’ passed a resolution to dissolve the union with Sweden.

The dissolution of the union between Norway and Sweden was a momentous event which was born from an apparently lesser dispute: a conflict over the question of a separate Norwegian consular service.

Norway and Sweden had their own cabinets and parliaments, but shared a single head of state, King Oscar II. But Norwegians always felt like the lesser party in the union: in fact they did not have their own foreign service missions, and were subordinate to Sweden in all matters of foreign policy.

A new sense of national identity was brewing in Norway and the Storting adopted a decision to establish an independent Norwegian consular service. For those not familiar with the subtleties of diplomacy, Embassies maintain relationships with the government and institutions of the host country, while consulates support citizens abroad. In practical terms, Norwegian expats and tourists had to rely on Swedish consulates.

King Oscar II refused to sanction the Storting’s decision. As a result, the Norwegian Government resigned. The King did not succeed in appointing a new government. This crisis meant that the union between the two Scandinavian countries was no longer effective. And that takes us to the 7th of June 1905, when the Storting assembly unilaterally voted for a dissolution of the union.

The Storting extended an offer to King Oscar II to appoint a prince from his own House of Bernadotte as new King of Norway. This gesture of goodwill would have relieved the tension now mounting between the two nations. King Oscar, though, formally declined the offer.

The Storting needed another candidate. An early version of LinkedIn would have tried to solve the issue via a mass mailing to thousands of unqualified applicants. But the Norwegian assembly was more effective and turned to another candidate much closer to home: our friend Prince Carl of Denmark. He clearly fitted the job description:

‘Job ID #1: Norwegian King and Head of State. The ideal candidate should fulfil the following pre-requisites:

- Male

- Military officer, preferably in the Navy, as they have the smartest uniforms

- Scandinavian, familiar with Norwegian language and culture

- Related to the house of Bernadotte, for example via his mother Louise, niece of King Oscar II

- With close ties with the most powerful nation on Earth, the British Empire, for example via marriage with a British Princess.

- Must have already sired a son, to ensure succession.

- Clean driving licence

- Good Excel and Powerpoint skills not essential but welcomed’

The offer was extended to Carl in Autumn of that year. The Danish Prince was not a power grabber and had great consideration for the will of the people. He was well-aware that the majority party in the Storting, the Liberals, were considering the idea of making Norway a Republic. So, he insisted that before accepting the crown, he should listen to the opinion of the Norwegian people: on his proposal, it was decided to hold a referendum on Norway’s future form of government.

The referendum was held on the 12th and 13th of November 1905. The result was almost 260,000 votes in favour of a monarchy versus almost 70,000 for the republic. This gave Prince Carl a clear popular mandate.

On the 18th of November, Carl found in his inbox a telegram pinged by the President of the Storting, formally offering him the Norwegian throne. Prince Carl happily accepted the offer, announcing that he would change his name into Haakon, while his son Alexander would be known as Olav, due to his love of the summer season.

The King’s choice of name was significant: in Old Norse, it translates as ‘High Son’ or ‘Chosen Son’, and it had been used by Norwegian kings centuries earlier, when the Country was independent. Haakon also adopted a personal motto: ‘Alt for Norge’ or ‘All for Norway’.

A Chosen Son for an Independent Kingdom

On the 25th of November 1905 Norway’s new royal family sailed into the capital Christiania – later Oslo – on the naval vessel Heimdal, named after the guardian God of Norse mythology.

Prime Minister Michelsen welcomed the new king with these words:

“It has been nearly 600 years since the Norwegian people have had a king of their own. Not in all this time has he been solely our own. We have always had to share him with others …

Chosen by a free people as a free man to lead this country, he is to be our very own. Once again, the king of the Norwegian people will emerge as a powerful, unifying symbol of the new, independent Norway and all that it shall undertake.”

I so would love if this speech was followed by knights chanting “The King in The North! The King in the North!”

But it didn’t. These were serious guys. The speech was followed by a salvo of cannons and church bells ringing throughout Oslo.

On the 27th King Haakon swore an oath of allegiance to the constitution.

On 22 June 1906, King Haakon and Queen Maud were crowned in Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim. Once again Haakon showed to be a king of the people: well-aware that the custom of the coronation was considered to be archaic and undemocratic by many citizens, he opted for a subdued ceremony. For instance, the traditional lavish procession previously staged by the Bernadottes was eliminated: the King and Queen were escorted to the cathedral in a single coach drawn by four horses.

The travel itself to Trondheim was conducted with little ceremony by train and carriages, with many stops along the way so that Haakon and Maud could get acquainted with the people of their new country.

Once they arrived at Nidaros Cathedral they were welcomed by 2,300 attendees and by the two Bishops who were to perform the ceremony: Bishop Wexelsen of Nidaros, and the wonderfully named Bishop Bang of Oslo. That was his real surname, look it up.

Bishop Bang greeted the King with the words:

“May the Lord bless your going in and your coming out now and for evermore.”

Very appropriate for Bishop Bang. I will stop there before I am sent to Hell.

Immediately after the coronation King Haakon immersed himself in Norwegian politics and culture. Polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen introduced the Royals to the national sport: skiing.

King Haakon also started new traditions, such as the much-loved annual children’s parade. But besides these rare popular celebrations, he and Maud showed great moderation, especially in comparison with other royal families of the time. The Royal Court was small and expenses were kept to a minimum.

This was yet another sign of Haakon’s political sensibility. Well-aware that more than 20% of the nation had republican sympathies he felt it important to maintain a modest lifestyle. This moderation was also in line with Norwegian tradition and respected the fact that Norway was not a wealthy country at that time. Today the country is the 8th largest producer of oil worldwide and 3rd largest producer of gas, but the first drillings were still decades away.

King Haakon was also wary of respecting the Norwegian constitution, to which he had sworn an oath of allegiance. He firmly believed that political power should be in the hands of democratically elected representatives, but he still wished to be kept closely informed about political affairs by the Government. Although he might state his views on a certain case, he always deferred to the majority in the Council of State, unfailingly supported policy decisions, and was careful never to show an affinity for any political party.

During his first years on the throne, Haakon oversaw important reforms, such as the institution of universal female suffrage in 1913. But a testing ordeal was just round the corner: WWI.

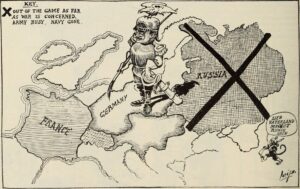

The Neutral Ally

In the years preceding WWI, Haakon’s Foreign Minister Jørgen Løvland outlined Norwegian foreign along two directives: neutrality, in combination with an active trade policy. Neutrality eschewed political alliances that might drag the country in foreign wars, with the implicit agreement that Norway was within the British sphere of influence. The government expected the British Empire to defend the young country in case of foreign aggression.

When Germany declared war on Russia on 1 August, Norway, along with Sweden and Denmark, issued a declaration of neutrality. The next priority for the country was to provide supplies, feed the population and maintain economic stability.

This led to a difficult balancing act for the Norwegian government: on the one hand, trade with Germany was vital for the country’s economy; on the other hand, the UK pressured Norway to become a part of the economic blockade of Germany.

In the spring and summer of 1915 Germany started to buy huge quantities of one particular supply from Norway: fish. Tons of fish, any fish related item they could get hold of.

The result? There was hardly any fish left for Norwegians. Cod was out of stock! Salmon was out of stock! Haddock was out of stock! Stock fish was out of stock!

The Irony!

Fish stocks were out of fish! I think I made my point.

What little fish was available was incredibly expensive. In an attempt to quell exports to Germany, Britain decided they would buy Norwegian fish instead. This decision decreased even more the availability and affordability of a vital food supply, while flooding Britain with stocks of Norwegian stock fish.

In Autumn 1916 life was dire for Norwegians. To continue with the fishing theme, they were caught between a rock and a hard plaice.

On one side, the German Navy had extended their unrestricted submarine warfare to the Arctic Sea, sinking several Norwegian merchant ships trading with Russia. On the other side, Great Britain had imposed an embargo on coal imports, as leverage to prevent Norway from selling copper ore to Germany.

Haakon and Maud were not oblivious to the plight of their people. In addition to conducting an even more frugal lifestyle, the Royal Couple established a fund to assist citizens in extremely difficult circumstances.

Luckily for the country, the Norwegian and British governments reached a deal, the ‘Tonnage Agreement’ in February 1917. This was a very clever set-up: first, Britain would lift the coal embargo; in exchange, Norway would suspend trade with Germany and supply the Entente instead. The Norwegian merchant ships would travel in convoys protected by the Royal Navy, reducing the risk of sinking by the Kaiser’s submarines. The clever bit was that the agreement was signed by the Norwegian Ship Owners Association, which camouflaged the Norwegian Government’s involvement allowing to preserve a formal neutrality. Hence, Norway became known as ‘the neutral ally’.

The positive effects of this agreement, though, did not reach all levels of society immediately. In June 1917, ordinary citizens were still struggling to cope with a cost of living that had increased by 250% since the start of the war. Over 300,000 people took to the streets in June to demonstrate against a lack of food and money to pay for necessities – roughly one seventh of the overall population! The government did not fall, although this crisis led to a radicalisation of the Labour Party, whose members even considered revolution as an answer.

Between Two Wars

Luckily for Haakon, the revolution did not take place, rather an evolution of the electoral system in 1919 which ensured a fairer representation of the working classes. Years later, in 1927, this reform led the Labour Party to winning the majority at the Storting. In 1928, Haakon resisted pressures to form a government led by the conservative ‘Agrarian Party’ and respected Labour’s majority by appointing its leader Christopher Hornsrud as Prime Minister.

The conservatives were not happy about this decision, but it would take only three years for the Agrarian Party to return to power. Amongst their ranks, a former military attaché, now Defense Minister, became very active in using the armed forces to quell union strikes and keep the spectre of Bolshevism at bay. His name was Vidkun Quisling.

I warmly invite you to watch our Biographics episode about Vidkun Quisling, to learn more about how he became the Nazi collaborator by definition, a traitor of his own country, the man who welcomed an invasion so he could be Prime Minister. Or

‘The Man Who Sold the Fjord’

if you like. As a quick summary: Former Defense Minister Quisling founded the National Union party in May 1933, modelling it after the Nazi and Fascist parties. Defeated in two consecutive elections, Quisling forged a friendship with Hitler’s advisor Alfred Rosenberg and exploited these ties to facilitate the German occupation of Norway.

But during the 1930’s these schemes had not yet become a source of worry for King Haakon, he had to face more personal issues. On the 20th of November 1938, his beloved Queen Maud died in London after a prolonged illness, while visiting her British relatives. Maud was buried in the Royal Mausoleum at Akershus Castle.

Apparently shy in public, Maud was known for being warm and vivacious with family and friends. Her original personality set her apart from other Queens of the time: she enjoyed outdoor activities like riding or skiing, more than court protocol, was a keen dancer and a competent photographer, and was directly involved in Prince Olav’s upbringing. Haakon would surely have loved to have her by his side during his – and his country’s – darkest hour: the German invasion of April 1940.

The Voice of the Resistance

In our Quisling video we cover in detail the invasion of Norway, the country’s resistance efforts and its eventual liberation. Today I will talk about the same events, but from Haakon’s perspective.

An occupation of Norway was part of the III Reich’s strategy, as the country could provide the German war effort with iron ore and an extensive merchant navy. It would have happened regardless of Quisling’s scheming to facilitate the German invasion, hoping to be installed as Prime Minister.

German troops invaded Norway on 9 April 1940. The heavy cruiser Blücher sailed into the Oslo fjord in the early morning hours of that day, transporting a landing force. Their task was to arrest the King and the members of the Government to compel Norway to capitulate immediately.

But the Norwegians were no pushovers.

The Fjord was protected by the cannons of the Oscarsborg Fortress, as well as the torpedo batteries in Kaholmen Island. They all opened fire on the Blücher and she sank at 06:22am with 1,300 sailors on board.

The sinking of the Blücher delayed the German troops’ advance on Oslo, giving the Royal Family, the Government and the Storting representatives the time needed to escape to safety in Elverum, Eastern Norway. There, the Storting gave the King and the Government full authority to rule the country for the duration of the war.

On the same day, Crown Prince Olav ensured the safety of his family, by having his wife Märtha and their three children cross the border to Sweden. They then travelled to the US in August. Thanks to Martha’s friendship with Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, she became a sort of unofficial Norwegian Ambassador in Washington.

On the 10th of April King Haakon met with the German envoy, Curt Bräuer. The Germans demanded for the Government headed by Johan Nygaardsvold to step down. The King had to appoint a new government headed by Vidkun Quisling.

The King put forth the German demands in an extraordinary meeting of the Council of State in the village of Nybergsund. Haakon stated that he would not attempt to influence the decision of the Government in this matter, but that he could not comply with the German ultimatum. He would rather abdicate than have Quisling as Prime Minister.

Without directly imposing his will, the King had managed to influence the decision of his ministers into rejecting Quisling. Upon learning of the King’s refusal, German forces repeatedly bombed Nybergsund, but he and Olav managed to escape to safety.

On the 15th of April, the first Allied landing party had arrived in Narvik. A combined Anglo-French-Polish force would support the Norwegian Army in engaging the German troops. But the Allies were ill-prepared for mountain warfare and the Luftwaffe had complete air superiority. By the end of May, the British cabinet had decided for a total retreat to avoid losing the whole expeditionary force to the Germans.

King Haakon was left with a difficult choice. Fleeing or staying? Staying by his people would have seemed natural, but the Germans were not hiding their intentions to have him captured. He could have been forced to provide legitimacy to Quisling’s government.

In the end he decided to flee the Country: he would establish a Government in exile in London, from where he could denounce Quisling or any other collaborationist cabinet, and lead the resistance effort.

On 7 June 1940 the King, the Crown Prince and the Government travelled from Tromsø to England. On the 9th, Norway had surrendered. The Norwegians and their allies held out for two months against a German invasion, longer than any other country except for the Soviet Union. As I said: no pushovers.

From London, King Haakon became the foremost symbol of the Norwegian people’s will to fight for a free and independent Norway, and his radio broadcasts from London served as a source of inspiration for young and old alike.

Back in Norway, the Germans had realised that Quisling was an unreliable leader with little popular support. The reins of the country were effectively taken by Reichskommissar Josef Terboven.

He attempted to establish a legal occupation government, elected by the Storting, to collaborate with the Nazis. But this required the King’s abdication. In a speech on the 8th of July 1940 Haakon once again made clear that he would not give in to German demands, and that he was still the legitimate head of the Norwegian state.

On the 25th of September Terboven abandoned all plans to collaborate with the existing Norwegian authorities. He declared the King and the Government deposed and outlawed all political parties, except for Quisling’s National Union. All activities in support of the Royal Family were forbidden, but King Haakon and the government-in-exile stood firm in their resolve to fight until Norway was liberated.

Over the next five years, Haakon’s speeches would inspire daily, constant acts of civil disobedience against the German occupiers. Haakon’s monogram, a ‘7’ imposed on a capital ‘H’ became a symbol of defiance. Haakon also inspired the creation of the Milorg – or Home Front. This resistance movement was a constant thorn in the Nazis’ side: it worked closely with the Special Operations Executive and was responsible for the destruction of the Telemark plant, which stalled German research on the Atomic bomb.

By the end of the War, Norway was garrisoned by approximately 400,000 German troops, 1 soldier for every 6 citizens. This gives an indication of how difficult it was for the Reich to tame the Norwegians. Did I mention that these guys were no pushovers?

Return of the Chosen Son

Germany capitulated on 8 May 1945. Terboven committed suicide on the same day, while Quisling was trialled and executed in October.

King Haakon returned home on the 7th of June, the fifth anniversary of his escape to London. In late summer 1945 he embarked on a tour of the country to see for himself the destruction caused by the war, as well as to encourage the ongoing efforts to rebuild infrastructure.

The Norwegians were happy to have their King back, and grateful for his resolve during the ordeal of the War. A collection was launched to raise funds for a special 75th birthday present: A Royal Yacht. King Haakon accepted this gift in 1947 and re-christened the vessel the Norge, which he used in many official visits abroad. Haakon continued to maintain strong ties with the UK, even after Maud’s death. During one of his visits to London, he attended a theatrical performance of ‘The Moon is Down’, by John Steinbeck.

The original novel was published in 1942 as a means to encourage resistance in Nazi occupied countries, and its setting, characters and plot were based on the invasion of Norway. One of the protagonists is the elderly, calm, authoritative Mayor Orden, who encourages his citizens to disobedience and open rebellion against the invaders. It is not difficult to find Haakon’s influence on this character and on his opposition to the treasonous shop keeper Corell, a Quisling in disguise.

After 52 years on the throne, aged 85, King Haakon VII died at the Royal Palace in Oslo on the 21st of September 1957, and was buried at Maud’s side, in the Royal Mausoleum at Akershus Castle.

I hope you enjoyed today’s Biographics. As a final thought, I will leave you with Haakon’s dilemma: would you have stayed in Norway, by your people, and risk giving legitimacy – even involuntarily – to Quisling and Terboven? Or would you flee the country like he did? And a small quiz for you: can you name an European royal who decided to stay after the German invasion? Post your answers and opinion in the comments, and as usual … thank you for watching!